Pokpoam Hermitage – 폭포암 (Goseong, Gyeongsangnam-do)

Hermitage History

Pokpoam Hermitage, which means “Waterfall Hermitage” in English, is situated to the south of Mt. Gujeolsan (564.5) in northeastern Goseong, Gyeongsangnam-do. Pokpoam Hermitage is situated on the former temple grounds of Sadusa Temple. Sadusa Temple was used as a site for the manufacturing of arrows for the Righteous Army led by Samyeong-daesa (1544-1610). The temple was destroyed, when it was burned to the ground by the invading Japanese army during the Imjin War (1592-98). The temple would remain abandoned until 1981, when the monk Hyeongak came to Goseong to pray for one hundred days. It was around this time that tiles and the foundation for the former Sadusa Temple were discovered.

As for the name of the hermitage, there’s a rather interesting legend connected with it. There’s a waterfall that flows through the hermitage named “Yongho-pokpo – 용호폭포.” According to this legend, there used to live an evil dragon that resided in the pooling water beneath the waterfall. One day, it ascended up into the sky. However, at the same time that the dragon was flying, local women were gathering food in the valley. The dragon was curious, so it tried to hide to spy on these women. Suddenly, lightning struck and the dragon was shattered into various pieces. Its body would become a rock that surrounded the Yongho Waterfall like a folding screen. The waterfall would flow over the dragon’s head, which gives it its name of Yongho Waterfall. And it’s internal organs dissolved to become a cave. A tiger came to live in this cave, and the cave came to be known as the Baekho-gul Cave. Currently, it’s used as a Sanshin-gak Hall at the hermitage. As for the dragon’s horns, they became a rock at the top of Mt. Gujeolsan, and its eyes became Bodeok-gul Cave to the left of the waterfall. Currently, this cave is off-limits to the general public. The Bandal-gul Cave at Pokpoam Hermitage, which is currently used as the Yongwang-dang Hall, is said to have mysterious mineral water flowing from it. Lastly, the dragon’s tail was cut off and caught on a rock to make part of the rock formation around the hermitage.

In addition to this legend, the temple is really popular because it’s said that the Yongho-pokpo Waterfall makes people’s wishes come true. It’s also popular among hikers, so Pokpoam Hermitage is doubly busy so be prepared and probably visit the hermitage at an earlier hour.

Hermitage Layout

You first approach the hermitage grounds from the parking lot. The pathway zigs and zags at a pretty steep angle over 300 metres, until you finally arrive the base of the pooling waterfall. Along the way, you’ll pass by some rather curious pagodas with various images at their bases like hearts, stars, frogs, and even a moktak.

Depending on when you visit the hermitage, the waterfall can be quite intense or a slow trickle of water. And above the waterfall is a suspension bridge up near the peak of the mountain. But back at the base of the waterfall, you’ll notice an outdoor shrine dedicated to Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion) that consists of a five metre tall statue of the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Continuing up the stairs that led you to the outdoor shrine dedicated to Gwanseeum-bosal, there will be an exit to your right. Continuing along this trail, you’ll come to a rock where you can come quite close to the flow of the falls. And on days where the waterfall is really flowing, you can get quite wet from all the mist in the air. Take your time and enjoy the waterfall from up-close.

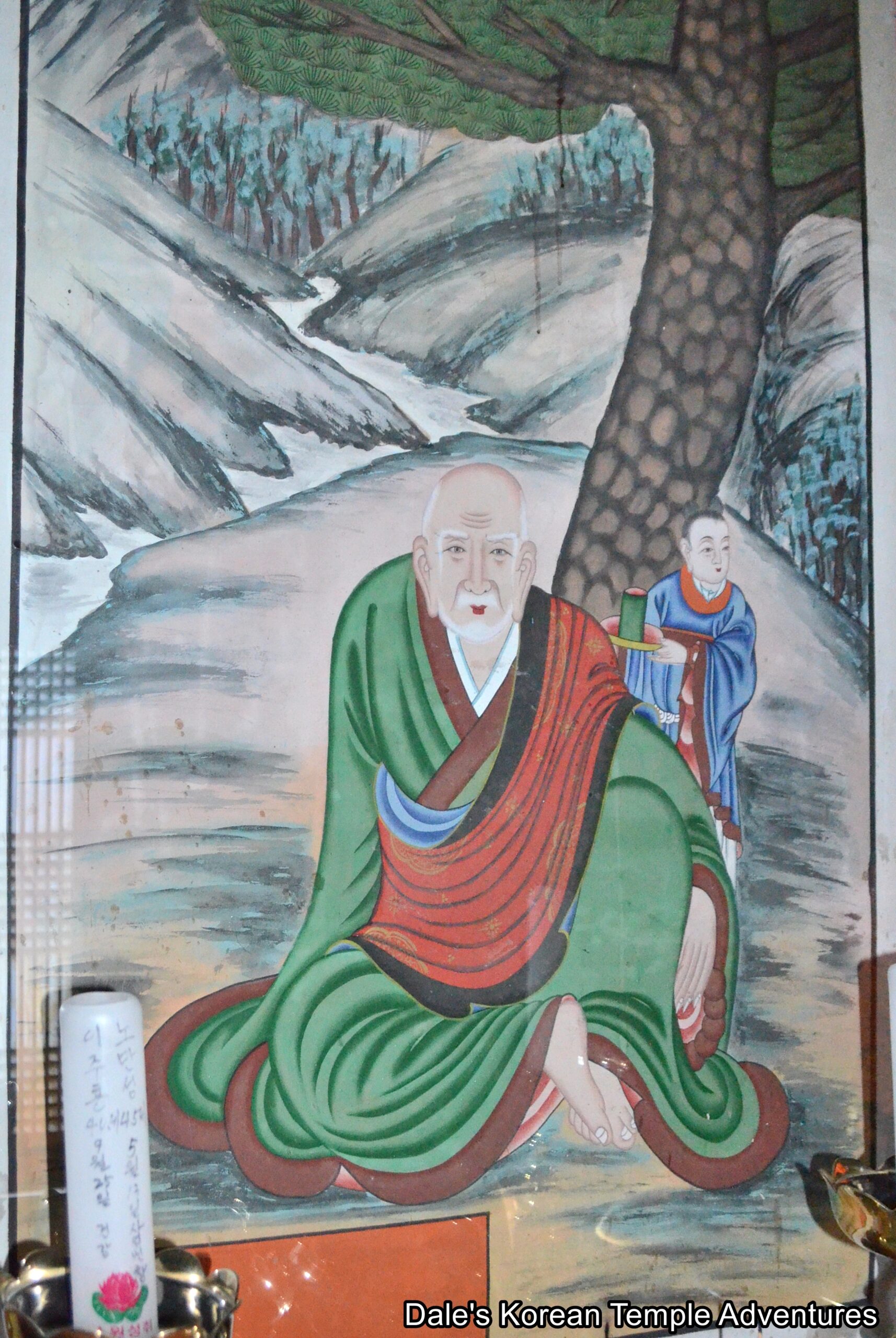

Climbing up the set of uneven stone stairs, you’ll next come to the Yongwang-dang Hall, which is also known as the Bandal-gul Cave. The outdoor of this structure is a modern cement structure with fading paint. Stepping inside the cave, you’ll find a small statue on the main altar dedicated to Yongwang (The Dragon King). And this red main altar image of Yongwang is backed to the side by a print of a black dragon. Also in this area is a row of clapboard buildings. The entry to the far left is the entrance to the Gwaneum-jeon Hall at Pokpoam Hermitage. Standing inside this cave-like interior is a golden image of Gwanseeum-bosal on the main altar.

Back at the stairs that led you up towards these structures, but hanging a left this time, you’ll find a collection of structures. The first is the hermitage’s kitchen and administrative office. Above this, and up on the next level of the large ledge, is the Daeung-jeon Hall. The exterior walls of the main hall are adorned with a collection of paintings that include a white image of Gwaneeum-bosal and Bicheon (Flying Heavenly Deities). Stepping inside the main hall, you’ll find a triad of statues on the main altar. The central image, rather surprisingly, appears to be that of Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise), who is joined on either side by Gwanseeum-bosal and Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). And hanging on the far right wall is a modern, black accented, Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural).

To the left of the Daeung-jeon Hall, you’ll find a golden relief of Yaksa-yeorae-bul (The Buddha of the Eastern Paradise, and the Buddha of Medicine). This image holds a medicinal jar in its left hand, as it looks out towards the valley below.

Beyond this golden relief, you’ll find numerous sets of stairs that lead up and around to the suspension bridge above the hermitage’s waterfall. Along the way, you get beautiful views of both the waterfall and the valley below. Both are equally stunning.

Eventually, you’ll come to a clearing, where you’ll find the rather long suspension bridge. If you feel up for a hike, you can continue across the bridge to the other side and hike around Mt. Gujeolsan. However, if you don’t have the time or inclination, you can simply get great pictures of the hermitage grounds and valley below, or the waterfall from above. Either way, and whatever you might choose, the views from the heights of the suspension bridge are stunning.

How To Get There

The easiest, and least complicated, way to get to Pokpoam Hermitage from the Goseong Intercity Bus Terminal is to take a taxi. This is especially the case if you’re with a group. In total, the taxi ride should take about 20 minutes, over 12 km, and it’ll cost you around 20,000 won (one way). Otherwise, you’ll be on a bus for about 40 minutes, and then need to hike for over 70 minutes, or 4 km, to get to Pokpoam Hermitage.

Overall Rating: 6.5/10

Pokpoam Hermitage in Goseong, Gyeongsangnam-do is pretty tricky to rate. If you simply leave it to the shrine halls at the hermitage, it’s rather pedestrian. However, once you include the waterfall, the valley, and the scenic mountain, it only helps to elevate the hermitage. So depending on what you might enjoy at a temple, whether it’s nature or shrine halls, it’ll go a long way in determining just how much you enjoy Pokpoam Hermitage. Either way, however, Pokpoam Hermitage makes for a nice little trip in the countryside of Goseong. But be forewarned, it can get quite busy.

Recent comments