Introduction

At the very heart of Japan’s Colonial interest in Korean Buddhism was where the religious and secular met, where Koreans and Japanese interacted and came into conflict, where preservation met exploitation, and Mt. Namsan in Gyeongju was at the very heart of this debate that took place during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-45).

There are numerous reasons as to why the Japanese Colonial authorities took an interest in Korean Buddhism. The first of these four reasons is Japan believed that Buddhism was a legitimate and natural counterpoint to help check future encroachment by Western Christianity. And because Korea’s history was so rooted in Buddhism, it would help function as a common bond between the two people that furthered Japan’s “Great Asian Co-Prosperity” policy. However, this common thread would ultimately be dictated by the policies of Japan; not only towards Korea, but Asia as a whole.

The second way in which Buddhism would be used by the Japanese was that Buddhist sculptures were thought to be the pinnacle of Asian art in much the same way that Greek and Roman sculptures are thought of in Western art. This interpretation of Buddhist art was first framed and created by Japanese art historian Okakura Tenshin (1863-1913), who was also known as Okakura Kakuzo, helped to approach Korean Buddhist art in the same way, as well.

A third reason for Japan’s interest in Korean Buddhism was that Japan conducted an extensive survey of their new colonized territory. This involved the surveying of Korea’s cities, villages, roads, hills, and mountains. And in these locations, the Japanese found Buddhist temples, temple sites, statues, pagodas, and various other objects of veneration. With this plethora of Buddhist locations and artifacts, it led to the colonial administration’s interest in restoring these locations and artifacts as part of Japan’s imperial agenda of cultural enlightenment. A juxtaposition was formed between the anti-Buddhist policies that took shape during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) and the steady decline and ruination of the nation with those of the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.). To the Japanese, the zenith of Korean culture took place during the Silla Dynasty, which also just so happened to have Buddhism as their state religion, and whose capital was located in Gyeongju. So the decline of Korea could be blamed on the anti-Buddhist policies of the Joseon Dynasty (who Japan had just overthrown), while the savior of Korea’s golden past in the form of Silla and Gyeongju would benefit the Japanese through conservation and reconstruction.

And the fourth and final reason that Japan took such a keen interest in Korean Buddhism was for the newly burgeoning tourism industry both in Japan and Korea. This industry was made possible in Korea with the rise of the extensive railway network built by Japan. With this newly developed and developing railroad network, Japanese authorities sought out scenic locations in Korea so that Japanese tourists would want to explore the Korean Peninsula. And because Gyeongju was so deeply rooted in Buddhism through its temples, temple sites, pagodas, and statues, and because Japan’s history was equally rooted in Buddhism, it made sense for Japanese authorities to help open up Gyeongju as a destination for Japanese tourists. By doing this, Japan would help generate revenue for future expansionist policies like in Manchuria, while also creating income for Koreans as a by-product of these expansionist imperialist policies.

So it’s to the setting of Gyeongju we first turn to better understand Japan and its interaction with Korean Buddhism through the guise of Mt. Namsan.

Gyeongju

In 1902, Sekino Tadashi (1868-1935), who was a Tokyo Imperial University-trained architect, came to the Korean Peninsula to survey the art and architecture of Korea. In total, he chose three locations for his field research. These three cities were Gyeongju (the ancient capital of Silla for nearly a thousand years), Kaesong (the capital of the Goryeo Dynasty for nearly five hundred years, and Gyeongseong (Seoul), which was the capital of the Joseon Dynasty for over five hundred years.

With all three cities in mind, and as to how and why Japan took such an interest in Korean Buddhism as a vehicle for its own goals and their subsequent policies, it makes perfect sense as to why Japanese authorities were so focused on Gyeongju and its past.

Gyeongju, as a tourist destination, was particularly rich in Buddhist art, temples, temple sites, and royal Silla tombs. Gyeongju evoked a certain sense of nostalgia in the Japanese. Japanese visitors to Gyeongju were typically reminded of Nara, which was Japan’s former capital. Another reason for Japan’s interest in Gyeongju is that there was a certain charm to the ancient city being in ruins, unlike Nara, which was still intact. For instance, Yasuda Yojuro, a famous Japanese writer, in his travelogue simply entitled “Keishu” (Gyeongju) of 1933 wrote, “The ruins of East Asia exist in Gyeongju…There is nothing comparable to Todai-ji, Horyu-ji, Yakushi-ji or Toshoda-ji of Nara. All are ruins and relics.”

Japanese government-sponsored researchers like Sekino Tadashi found that Gyeongju was the best place to promote the rhetoric attached to Buddhism through assimilation. One particular point of interest for these Japanese researchers was the mythical story of Empress Jingu-kogo (169-269 A.D.) and her purported invasion and rule over parts of the Korean Peninsula. The idea of Empress Jingu ruling over Korea fed into the narrative that Japan was, once more, returning to a place that they had once ruled. For this reason, the first generation of Japanese field researchers in Korea paid particular attention to royal tombs and excavating Silla burial artifacts, as well. This was all in pursuit of validating and legitimizing their most recent occupation of the Korean Peninsula.

With all of this in mind, and with art history as a focus of Sekino Tadashi, especially Buddhist monuments and statues, Sekino believed that these artifacts were a way of gauging the cultural achievements of a society. As a result, Sekino considered Silla to be the golden age of Korean art, since it was a time when Buddhist art obviously flourished. As early as 1895, and upon Sekino’s graduation from Tokyo Imperial University, he wrote his thesis on Phoenix Hall, which was an 11th century shrine hall in Byodo-in. Sekino was to write a book entitled “Korean Art History” (Chosen bijutsushi) in 1932, where he was to establish a framework that helped to develop Korean Buddhist art in terms of its historical context, level of achievement, and its relationship to other Asian nations like those found in Chinese Buddhist art. This connection would help bond China to Korea and Korea to Japan.

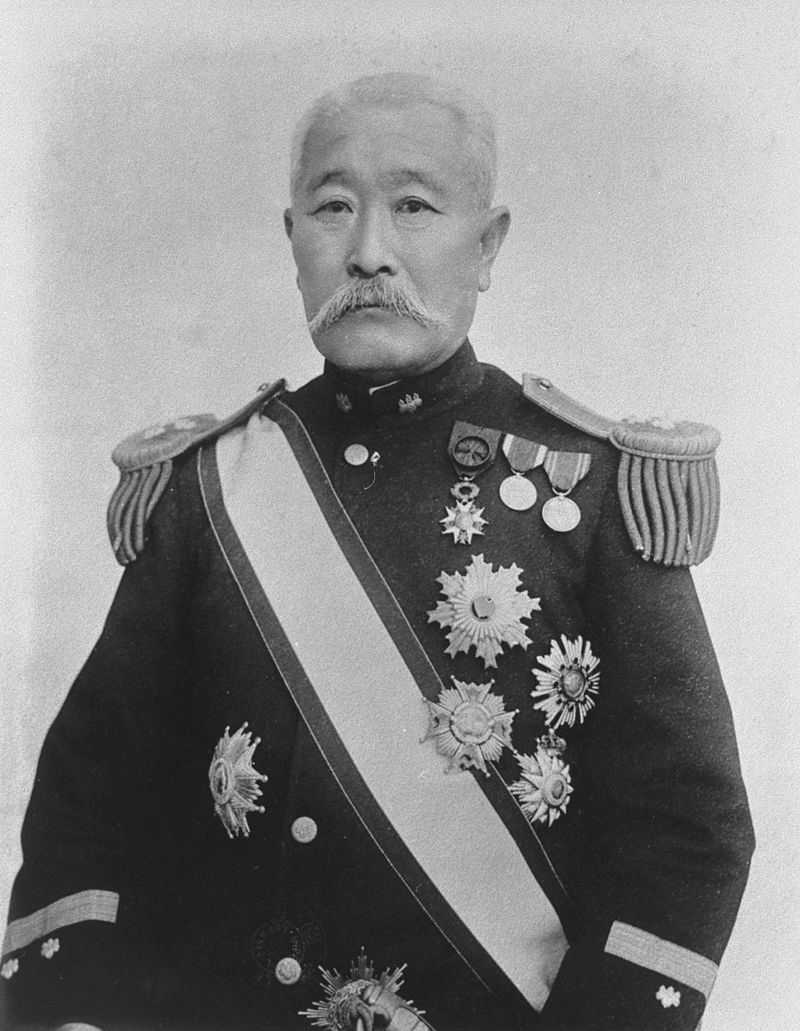

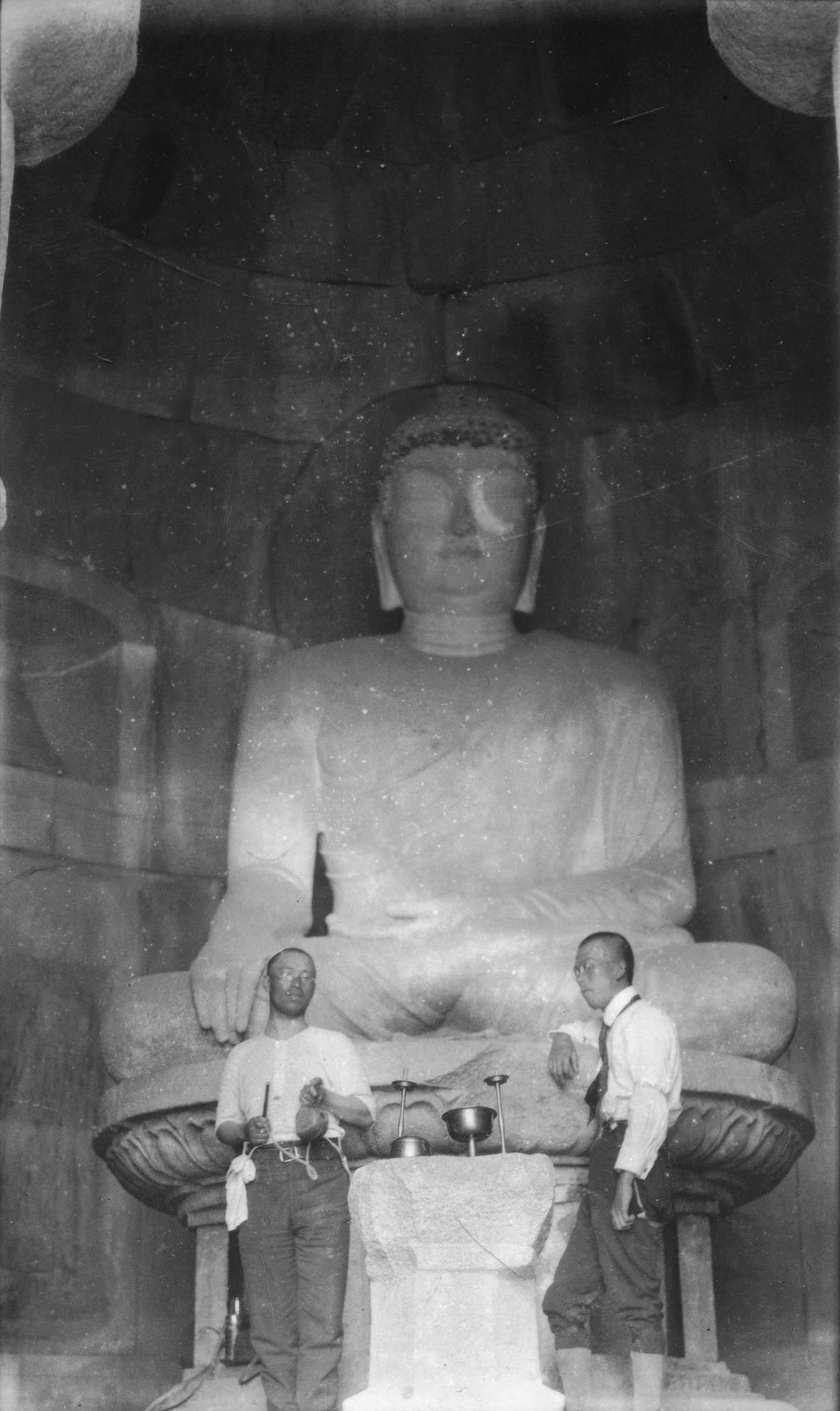

According to people like Dr. Sekino, the ultimate expression of Korean Buddhist art was the Seokguram Grotto. Ever since Sone Arasuke (1849-1910), who was the second Colonial Resident-General of Korea visited the Seokguram Grotto in 1909, it became the primary object of restoration for the Japanese authorities because it was a perfect expression and example of Korea’s glorious past, which had been lost during the Joseon Dynasty. It was this former splendor during the Silla Dynasty that Japan was hoping to restore for obvious political and propaganda reasons.

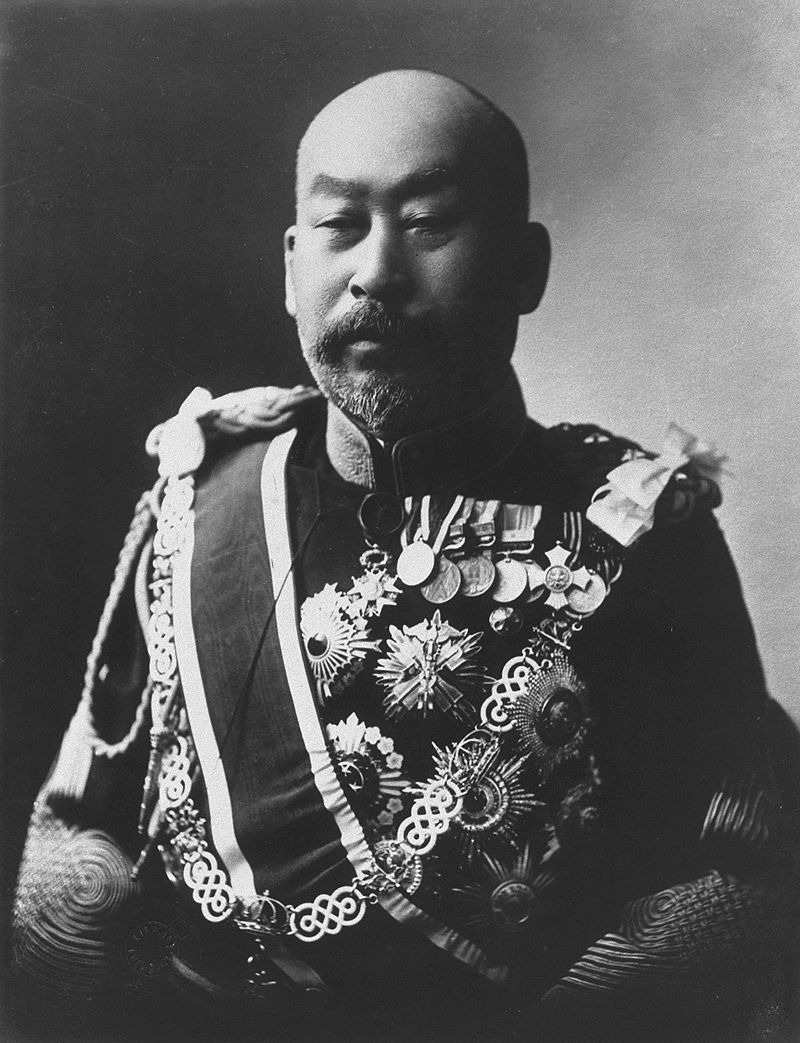

After Korea’s annexation by the Japanese in 1910, various Japanese groups became highly interested in historic sites in Gyeongju. A whole host of groups that included professionally trained archaeologists, ethnologists, anthropologists, and administrators were sent or emigrated to Gyeongju. This group would actively survey the most ancient of sites, temples, and artifacts of Silla in Gyeongju. These efforts took many forms like the “Silla Society” (Shiragi kai) which consisted of Japanese professionals and Korean locals. The “Silla Society” quickly became the “Society for the Preservation of Historical Remains of Gyeongju” (Keishu koseki hozonkai) in 1911. This “Society for the Preservation of Historical Remains of Gyeongju” received financial support from the start from the first Governor-General, Terauchi Masatake (1852–1919). This society would also receive support from high-ranking Korean officials, as well. This group was a purposely organized society that was led by Japanese administrators with the express goal of furthering Japanese pre-annexation objectives. And it’s to this that Japanese authorities approached Gyeongju.

Site Surveys on Mt. Namsan

With Gyeongju being a major focus of Japanese authorities, it was rather surprising that Mt. Namsan in Gyeongju, a holy site during the Silla Kingdom, did not initially draw the attention of the very same authorities like those at the “Society for the Preservation of Historical Remains in Gyeongju.” Even other Buddhist statues and monuments in Gyeongju drew reasonable attention in comparison to Seokguram Grotto. However, fieldwork on Mt. Namsan lagged behind other sites like Bulguksa Temple, Bunhwangsa Temple, and even that of the Gulbulsa-ji Temple Site. In fact, one could argue that Mt. Namsan was even neglected by comparison.

Below is a chronological outline of the recorded surveys conducted on various sites on Mt. Namsan and by whom and what they recorded during these surveys:

– 1902: Sekino Tadashi visited Mt. Namsan but only focused on the remains of the Namsan Fortress.

– 1906: Imanishi Ryu describes Namsan Fortress, the temple sites on both sides of the fortress, and ruined pagodas. However, his fieldwork was only partially completed.

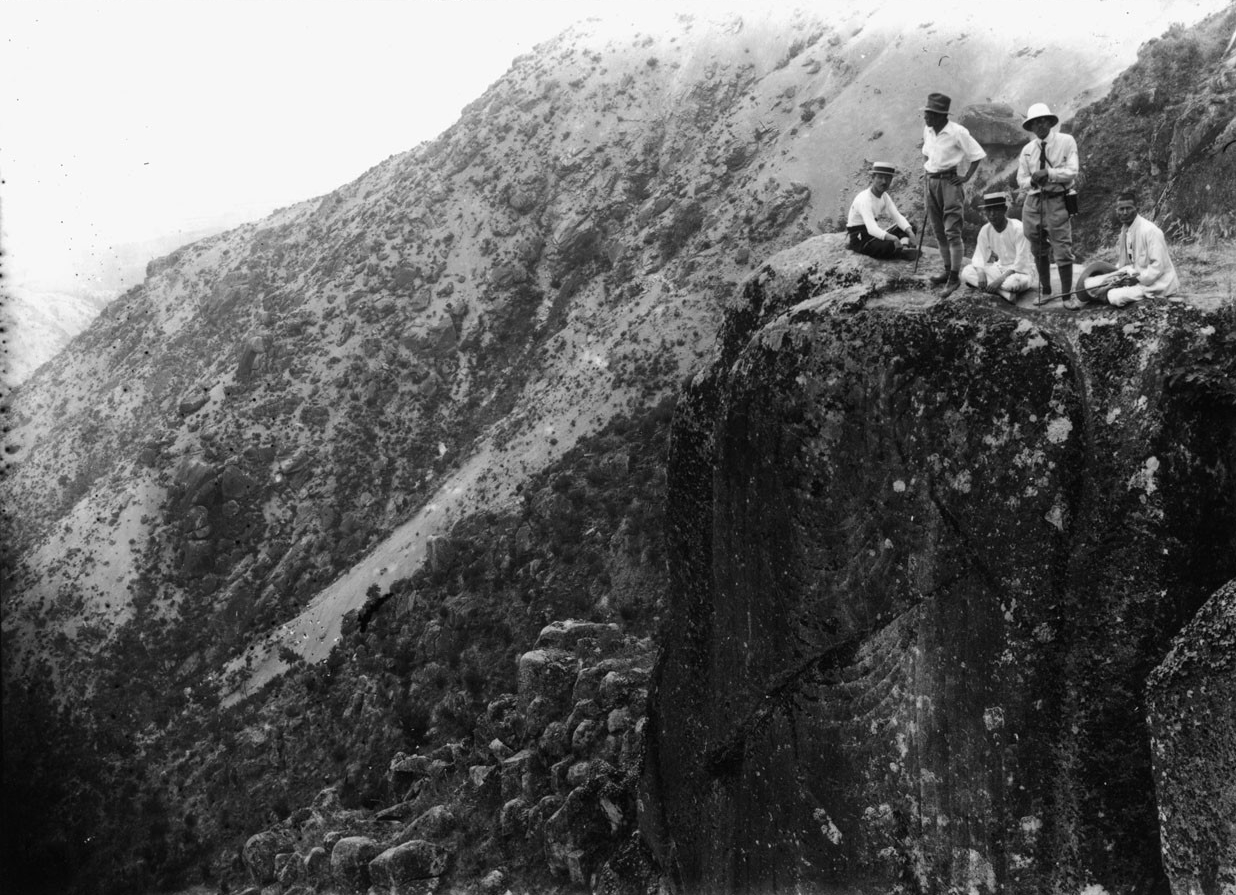

– 1909: Sekino Tadashi re-investigates parts of Mt. Namsan. Torii Ryuzo surveys the sites at the foot of Mt. Namsan. Together, they found urns, stone tools and earthen ware outside Namsan Fortress.

– 1915: the Stone Seated Bhaisajyaguru Buddha was moved out of Samneung-gol Valley and displayed at the Choson Industrial Exhibition in celebration of the five year anniversary of Japanese annexation of Korea.

– 1916: Moroga Hideo introduces 20 temple sites from Mt. Namsan in his “Study of Temples and Historical Remains of Silla.” Also around this time, researchers came to know that a group of tomb sites, Neolithic sites, Buddhist statues, pagodas, and stone lanterns existed at the foot of the mountain.

– 1920: Buddhist monuments of Mt. Namsan were introduced as part of a “Tourist Itinerary in Silla’s Ancient Capital of Gyeongju.”

– 1912-25: Photos and field reports on Mt. Namsan were completed by Moroga Hideo, Kodaira Ryozo, Osaka Kintaro and Tanaka Kamekuma. They were later published.

– 1923: Oba Tsunekichi, who was directed to examine the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong, became further interested in Mt. Namsan Buddhist sculptures. With Koizumi Takao, he discovered 4 additional monuments. They examined a monk-shaped statue on a three-story lotus pedestal at Yongjangsa-ji Temple Site.

– 1925: The “Colonial Forestry Experiment Institute” indirectly helped the Government-General Museum’s survey of the monuments on Mt. Namsan. Fujita Ryosaku participates in the measuring and taking photos of monuments. As a result, a few more Buddhist temple sites, statues, and pagodas were discovered.

– 1927-1928: The Government-General Museum, with the help of Tanaka Juzo, made a 1/5000 map of site locations on Mt. Namsan. He did this by consulting Gyeongju experts and surveying the entire mountain.

– 1932: Arimitsu Kyoichi and Imaseki Mitsuo stayed in a tent on Mt. Namsan for 10 days to survey and take photos of sites and monuments on the mountain. Based on this, new monuments were recorded with the help of investigations by Osaka Kintaro, Moroga Hideo, and Watari Fumiya. Another survey by Saito Tadashi and Fujishima Gaijiro confirmed even more Silla sites on the mountain.

– 1936-37: The “Research for Historical Remains of Korea” investigated statues on Mt. Namsan along with the Neungjitap Pagoda for King Munmu on Mt. Nangsan.

– Oba Tsunekichi conducted multiple surveys and small-scale excavations on Mt. Namsan. He measured monuments and took pictures with the help of Imaseki Mitsuo. He was aided with the support of Sawa Shunichi, Saito Tadashi, Tanaka Kamekuma, and Fujita Ryosaku. The whole project was supported by Arimitsu Kyoichi, Osaka Kintaro, Moroga Hideo, and Choe Sunbong. And he specifically thanked Osaka Kintaro for helping to match sites with their names.

By looking through these archaeological efforts, there are three things that stick-out. The first is that the mountain was recognized as a place where some historical sites from the Neolithic Period, the Bronze Age, and the Three Kingdoms period were located. In particular, the Namsan fortress from Silla was seen as particularly important. In this way, only the site locations, and not the mountain itself, is seen has having value.

The second area of attention according to these Japanese surveys on Mt. Namsan is that the mountain acted as a supplier of Silla Buddhist iconography. Statues and pagodas were viewed as being independent of Mt. Namsan. More specifically, Mt. Namsan was just their location, and there was no connection formed between the artifacts and their setting. As a result, when both cost and technology would permit it, the statues were moved from their original location; which, in turn, lost their original context and essential value.

The best example of removing a statue from their original location can be seen in the Stone Seated Bhaisajyaguru Buddha that was discovered on Mt. Namsan. The sculpture was first introduced to the world by Sekino Tadashi in 1911. This statue was removed from its original site on Mt. Namsan and moved to an exhibition in the Choson Industrial Exhibition in 1915 in the Gyeongbokgung Palace in Seoul. It was carefully displayed by attempting to recreate the Buddhist statues inside Seokguram Grotto. The seated statue was placed in front of a staircase at the center of the newly constructed museum. The way this was done was by placing two life-sized statues from another site in Gyeongju, Gamsansa Temple, along with replicas of the reliefs from inside Seokguram Grotto. Obviously the mixing and matching of various sites with various images didn’t bother the Japanese authorities. By doing this, the Japanese authorities were very obviously re-writing the way in which these images should and would be interpreted disconnected from their original context and meaning. And the reason for such a display is that the Stone Seated Bhaisajyaguru Buddha was to act as a substitute for the main Buddha inside the Seokguram Grotto simply because they were unable to move the original Buddha from inside Seokguram Grotto to Seoul even though several attempts had been made.

And the third reason for categorizing Mt. Namsan the way they did is that the mountain was valued as being a sacred realm. Over time, Mt. Namsan was finally recognized as being culturally important. This new approach was started and championed by Oba Tsunekichi in 1923. However, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the mountain was seen as a unified whole worthy of investigation and importance.

Osaka Kintaro and Mt. Namsan

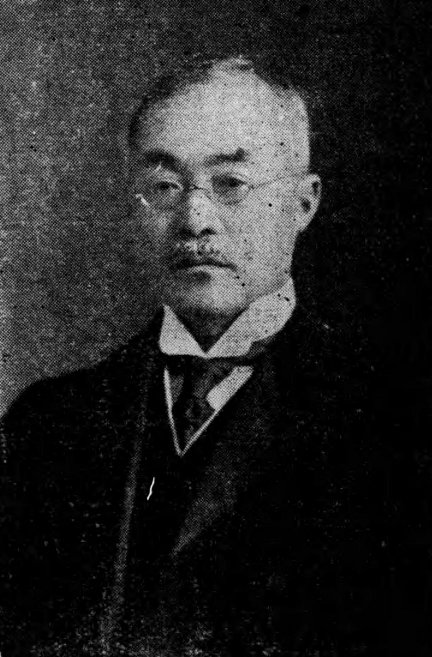

Of the various professionally trained archaeologists, ethnologists, anthropologists, and administrators, they had their various ways in which they approached Gyeongju and Mt. Namsan. For example, “In the Pastimes of Gyeongju,” Osaka Kintaro dedicated some 22 pages of the 250 pagoes of the text to Mt. Namsan in 1931.

Osaka recognized the importance of the mountain both as a source of archaeological ruins and as a site of active worship. Perhaps the best example of this is Osaka’s described discovery of the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong on Mt. Namsan. Upon arriving in Gyeongju in 1915, Osaka had already heard rumours of the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong. According to these rumours, the triad was almost completely buried in front of Poseok-jong. However, it wasn’t until 1917 that Osaka finally found the triad by following local children’s directions. Then in 1922, anticipating the royal visit of the Japanese Prince, the “Society for the Preservation of Historical Remains of Gyeongju” wanted to move the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong to their exhibition room. The reason they wanted to do this is that the exhibition room simply had a meager collection at that time of Silla artifacts. Due to the technical concerns of moving the weighty triad, Japanese authorities decided to leave the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong in its original location.

As to the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong as a living object of worship, when Osaka revisited the site, he saw that locals had stacked small stones in front of the statues, while making a wish. Osaka would go on to explain that what surprised visitors to Gyeongju wasn’t Cheomseongdae or even the royal burial tombs, rather, “it has to be the legendary Mt. Namsan that was a background for countless sites and solely stood picturing a thousand years of fluctuations between glory and decline.”

In the foreword of Osaka’s “In the Pastimes of Gyeongju,” on the other hand, we have Fujita Ryosaku state that Gyeongju of Korea had shifted to become a Gyeongju of Japan. And ultimately, it would become a Gyeongju of East Asia. These comments express the overall colonial intentions of Japan with Gyeongju (and Korea as a whole). Korea and Koreans would be assimilated and used for Japanese purposes.

This sentiment wasn’t new, however. This was a decades old idea that was first stated and written about in 1912 in the “Government General Monthly” (Chosen sotokufu geppo). This monthly periodical states, “the ancient remains of Gyeongju do not merely represent the pride of Gyeongju; they are indeed the pride of Korea, then it should be the pride of our empire.” This quote emphasizes a few things. First, it emphasized the role that the colonizers now had over the territory they now occupied. As such, the colonizers now assumed the role of guardian of what they had looted. In the above comment by Fujita, Mt. Namsan is a protective mountain for the Silla people, as well as the Buddhist abode of Tusita. Additionally, the mountain was regarded as a place of Silla Buddhist art. So with his comments, Fujita is positioning Japan as the keeper of not only Korean Buddhist art, but also the keeper and interpreter of the entire East Asian Buddhist tradition, as well.

In addition to this religious and artistic ideology, Osaka also praised Mt. Namsan as “the climax of any tourist’s visit to Gyeongju.” The concentrated presence of pagodas, statues, temples, and temple sites, made it perfect for tourists. So much of Silla’s glorious past was concentrated in a small area in the southern part of Gyeongju.

One other interesting note about Osaka Kintaro is that he continuously compared the stone statues on Mt. Namsan with those found at Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto. Rather surprisingly, he valued those on Mt. Namsan more than he did of those on Mt. Tohamsan. And the reason for this, according to Osaka, is that both Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto represented the zenith of Silla Buddhist art. It is only after the creation of the iconography at these two locations on Mt. Tohamsan that there was a decline. As for Mt Namsan, on the contrary, the statues still exuded the true energy of Silla Buddhists. What’s interesting about this assessment by Osaka is that he draws a rather obvious line between the “art” of Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto and the “religion/faith” of Mt. Namsan. While this gap narrows more and more in the subsequent colonial years, the distinction was still being made at this early stage of exploration in Korea; and more specifically, in Gyeongju and Mt. Namsan.

Fujita Ryosaku and Mt. Namsan

Another interesting academic figure is Fujita Ryosaku. One week in 1925, Fujita, who was serving as a director of the Government-General Museum, participated with other surveyors in measuring and photographing sites, pagodas, and statues on Mt. Namsan. Together, they discovered several new artifacts and monuments. What’s most interesting about this fieldwork is that Fujita seized upon the “Forest Experiment Station” project on Mt. Namsan. The “Forest Experiment Station” was to be used as a central hub in expanding the network of nurseries in Korea. Only through the “Forest Experiment Station” was Mt. Namsan fully surveyed. This survey was only made possible in 1925 in cooperation with the better-funded forestry project. It was only through Japan’s love of forests and nature and its funding that Mt. Namsan was finally and fully explored and surveyed.

As a result of this survey, numerous things were discovered. For example, some sites on Mt. Namsan were under private ownership. Specifically, the Stone Seated Buddha in Mireuk-gok Valley of Namsan Mountain, for example, couldn’t be moved from its original site since it was located on private property; despite the fact, that the statue itself was state property. In contrast, the Stone Seated Bhaisajyaguru Buddha was moved to Seoul because there was no private ownership over the artifact. The reason for this, as a whole, is that most of Mt. Namsan was classified as a forest.

With this in mind, it can be argued through Fujita’s example that Colonial Japan wasn’t a unified monolithic organization. Instead, there were different approaches to different things like Gyeongju, Mt. Namsan, and conservation. Some Japanese that had lived in Gyeongju had different goals for their discoveries of sites and statues which could be independent of the Government-General. For instance, a Japanese professionally trained archaeologists, ethnologists, anthropologists, and/or administrators might pursue an academic discovery, while another might want an administrative promotion, while another might be pursuing monetary gain. And some might even be attempting to serve the Japanese colonial agenda. It was a mixed bag of motivations. And yet, at the very core of Japanese enthusiastic efforts, it was all backed by the threat of colonial violence to achieve certain goals. This is yet another wrinkle to the Japanese Colonial experience in Korea from 1910-1945.

Oba Tsunekichi and Mt. Namsan

Yet another academic and artist that has a connection to Gyeongju and Mt. Namsan was Oba Tsunekichi (1878-1958), who first came to Korea in 1916. He worked with Sekino Tadashi in making replicas of Goguryeo tomb murals. As an artist, he was an employee of the Government-General of Korea. Oba first became interested in Buddhist statues on Mt. Namsan in 1923, when he was sent to investigate the Stone Standing Buddha Triad in Bae-dong and the Yongjangsa-ji Temple Site with its three-story lotus pedestal. He would follow this up with several additional survey and small-scale excavations on Mt. Namsan.

One of the more interesting highlights to his endeavours on Mt. Namsan concerned the broken stone pagoda of the Changnimsa-ji Temple Site. Oba is quoted as writing about the pagoda of the Changnimsa-ji Temple Site, “The pagoda made in high-quality granite is located at the temple site in the center of the hilltop. Its scale and skillful construction make it the best pagoda on Mt. Namsan, and one of the biggest stone pagodas of Silla. It is lamentable that some parts are missing even from the previously toppled-down state. However, major parts still lay horizontally on the spot. The remnants of the first-story body and the roof stone, albeit broken, remained layered in order. Although the second and third-story body and those above the dew-basin are missing, surviving monumental stone slabs evoke the beauty of the destruction.” This was written by Oba in the “Illustrations of Korean Antiquities” (Chosen sotokufu) in 1940. This quote highlights the Japanese desire to see the beautiful in a monument that had been destroyed. The elevation of ruins as art was an early 19th century concept. This concept would permeate the tourists experience when visiting Gyeongju and the desire to discover the ruins of Silla.

But while the fragments of broken artifacts were being lauded by tourists and academics alike towards Gyeongju and Mt. Namsan, there was also praise for the ability of the Japanese to restore broken statues like the Stone Seated Bhaisajyaguru Buddha. Oba lamented in 1923 that only the octagonal lotus throne remained in its original location, whereas the Buddha’s body was toppled over in front of the base, the mandorla had fallen off of its back, and the Buddha’s head was found far down the embankment. Finally, in December, 1923, the Government-General restored the statue. According to Oba Tsunekichi, the statue became “a luminous Buddha on Mt. Namsan, the worthy icon for worship by sentient beings.” In this quote, Oba is doing two things. First, he was agreeing with the Government-General’s overall policy of restoring broken statues; while at the same time, Oba was also advocating for the preservation of the artifact at its original location, especially if this location was situated on Mt. Namsan.

As for the Yongjangsa-gol Valley and the Yongjangsa-ji Temple Site, Oba Tsunekichi wrote, “the natural scenery and rock formations made this area resonate with the painting of the Buddha’s Parinirvana and a collection of ten thousand things. Naturally occurring rocks in odd shapes evoke the images of descending Buddhist deities, dragons, and phoenixes, which created the impression of Mt. Namsan as a Buddha’s abode, Maitreya’s [Mireuk-bul, the Future Buddha] Pure Land, and the site for Amitabha’s [Amita-bul, the Buddha of the Western Paradise] descent. Similarly, all the folklore and myths embedded in each valley and its name help convey the idea of Mt. Namsan as a residence for the Sakyamuni’s True Body. The vista of the stone pagodas and statues at the Yongjangsa site was said to resemble the panoramic unfolding of Mt. Sumeru, consisting of the miraculous heavenly touch integrated with exquisite human efforts.” Again, Oba wrote this in 1940.

It’s rather obvious with the above quotes that Oba Tsunekichi saw Mt. Namsan as something more than simply being the repository of Silla temples, temple sites, pagodas, and statues. There’s something lofty about his writing about Mt. Namsan. In this sort of context, Oba even believed that the statues of Chilbulam Hermitage surpassed even those inside the Seokguram Grotto. Besides his belief that the Seokguram Grotto’s statues had been diminished by the secularization of their icons, but Oba also believed that the statues at Chilbulam Hermitage were Buddhist masterpieces. They would have taken a long time to produce, since they were made from granite. This, to Oba, further testified to the strong faith and artistry required to produce something like at Chilbulam Hermitage. And fortunately for future generations, despites the sculptures at Chilbulam Hermitage being exposed to the elements, they still endured. Another added bonus to the mastery and preservation of the Chilbulam Hermitage statues were their remote location away from harmful human activity.

Here, for Oba, the harmful human activities meant the people of Goryeo; and more specifically, of the Joseon Dynasty. These two dynasties were oppositional to the Silla people in Oba’s mind. Oba marveled at the fact that a local randomly opened up a small hermitage called Chilbulam Hermitage in order to help protect the Rock-Carved Buddhas at Chilburam Hermitage in Namsan Mountain. And yet, Oba was saddened by the fact that the physical condition of the sculpture was changed by moving it to a different location. Of course, this person was Korean. Oba was opposed to any discretionary changes to Korean artifacts by Koreans that weren’t authorized by the Japanese Colonial government.

Conclusion

There were numerous reasons that the Japanese Colonial authorities took an interest in Korean Buddhism. The first is that it helped guard against Western encroachments both culturally and religiously. Another reason is that Buddhist art, generally, was viewed as the ultimate expression of Asian culture. A third reason for such interest in Korean Buddhism is the oppositional positioning of the anti-Buddhist Joseon Dynasty with that of the Silla Dynasty. And the fourth and final reason for such interest in Korean Buddhism was for tourism in the new colony.

The interaction that Japan had with Korean Buddhism is perhaps best exemplified in Gyeongju with a more specific focus on Mt. Namsan. In fact, the way in which Japanese administrators and authorities approached Mt. Namsan is emblematic of the way in which Japanese authorities dealt with the sites and artifacts found throughout the rest of the Korean Peninsula as a whole. For some, Mt. Namsan was seen as a living site for continued worship by local people. Another approach was that Mt. Namsan was a mysterious location separate from the secular world and art of places like Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Hermitage on Mt. Tohamsan. And a third approach was to simply steal, move, and store these artifacts under the watchful eye of the Government-Generals. All three approaches interacted, overlapped, and came into conflict. And Mt. Namsan was a microcosm for the way in the which the rest of Korea was occupied, manipulated and turned in on itself by the Japanese.

Thus, at the very heart of Japan’s Colonial interests in Korean Buddhism was disagreement, consensus, preservation, exploitation, and perseverance. And nowhere could this better be seen than in the examples found in the discoveries on Mt. Namsan in Gyeongju.

Recent comments