Temple History

Baengnyeonsa Temple is located in the southern foothills of Mt. Mandeoksan (412.1 m) in Gangjin, Jeollanam-do. And the temple looks out beautifully towards the bay and Wando off in the distance. The name of the temple means “White Lotus Temple” in English, and it’s believed to have first been constructed in 839 A.D. by Muyeom-guksa (801-888 A.D.). The original name of the temple, however, was Mandeoksa Temple. Gradually the temple fell into disrepair caused by the efforts of Japanese pirates that were pillaging the coastal areas throughout the Korean Peninsula. The temple was eventually reconstructed in 1170 by the monk Yose. The temple was further expanded and reconstructed in 1426, when the abbot of the temple, Haengho, carried out a second reconstruction. A large-scale reconstruction of the temple began in 1430 through the support of Grand Prince Hyoryeong (1396-1486). Grand Prince Hyoryeong would abdicated the throne to his younger brother, King Sejong the Great (r. 1418-1450). After Grand Prince Hyoryeong reliquished the throne, he lived at Baengnyeonsa Temple for eight years, while also touring the area. It’s finally in the 19th century that Mandeoksa Temple came to be known as Baengnyeonsa Temple.

Baengnyeonsa Temple is home to one Korean Treasure, the “Stele for the Construction of Baengnyeonsa Temple,” which is Korean Treasure #1396

Jeong Yak-yong (Dasan), Tea, and Baengnyeonsa Temple

Baengnyeonsa Temple has a rather interesting connection to Jeong Yak-yong (1762-1836) the poet and philosopher, who was also known under his pen-name of Dasan (Tea Mountain), and the 19th century tea revival that took place during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

With the sudden death of King Jeongjo of Joseon (r. 1776-1800) in the summer of 1800, the new king, King Sunjo of Joseon (r. 1800-1834) ascended the throne. The only problem with this is that King Sunjo was only 11 years old. As a result, the power of the throne shifted to the widow of King Jeongjo, Queen Dowager Kim, or Queen Jeongsun (1745-1805). Queen Jeongsun belonged to a group that were opposed to the reformist Namin group, who were often Catholic. During the reign of her husband, she had been powerless to confront this reformist movement. But now in power, she launched an attack against the Catholics in Korea, who were denounced as traitors and enemies of the state. The older brother of Jeong Yak-yong, Jeong Yak-jong (1760-1801), was the head of the Catholic community at this time. As a result, the older brother was one of the first to be arrested and executed in the spring of 1801. A month later, Jeong Yak-jong’s eldest son, Jeong Cheol-sang, would be executed, as well.

What does this all have to do with Jeong Yak-yong? Well, as the younger brother of Jeong Yak-jong, Jeong Yak-yong was exiled several months later to Pohang. While in Pohang, Jeong was interrogated and tortured. While being tortured, it was discovered that Jeong wasn’t a Catholic. This saved Jeong from being executed, but it didn’t save him from further exile.

Jeong’s exile began in the waning days of 1801. It was in December, 1801 that Jeong arrived in Gangjin, Jeollanam-do. Jeong arrived with no money and no friends. Because of his situation, he lived in the back room of a rundown tavern kept by a widow until 1805.

By 1805, Queen Jeongsun would die and King Sunjo of Joseon came of age. This brought an end of the violence towards Catholics in Korea. This allowed Jeong to move freely in the Gangjin area in the spring of 1805. It was at this time that Jeong traveled to Baengnyeonsa Temple. It was during this journey that he met the newly arrived abbot of the temple, Hyejang. The two talked and Hyejang realized who the visitor actually was. The two quickly became close companions.

Later in 1805, Hyejang made it possible for Jeong to move out of the tavern and take up residence at a small hermitage near Goseongsa Temple. Then by the spring of 1808, Jeong took up residence in a house belonging to a distant relative of his mother on the slopes of a hill overlooking Gangjin and the neighbouring bay. He would spend the next ten years in this house until the fall of 1818. This house still exisits, and it’s known as the “Dasan Chodang.” Additionally, the hill behind his house was known locally as Da-san, or “Tea Mountain” in English. Dasan is the name that Jeong is better known as. At his house, Jeong would teach students, write, and read from his library of over a thousand books. In total, Jeong would write over 500 works.

Eventually Jeong would return to the family home near the Han River in Seoul. Jeong would die in 1836.

As for Jeong’s relationship to the resurgence in the 19th century tea revival, it was while living in Gangjin, and through his friendship with Hyejang, that things would change. Hyejang had just arrived at Baengnyeonsa Temple from Daeheungsa Temple. For a few years, Jeong’s health had suffered due to poor nutrition. Jeong suffered from chronic digestive problems. And it was through tea that he was able to help alleviate some of these problems. So in a poem from Jeong to Hyejang in the 4th month of 1805, Jeong asks for some tea leaves from the hill above Baengnyeonsa Temple. Because of Hyejang having traveled to Baengnyeonsa Temple from the tea-rich environs of Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam, Jeollanam-do, it was once thought that Hyejang taught Jeong about tea; however, from a series of poems exchanged between the two, it seems as though it was Hyejang that learned how to make a kind of caked tea from Jeong.

In 1809, the monk Choui-seonsa (1786-1866), who was also from Daeheungsa Temple, came to Gangjin to visit Jeong for a few months. There, Choui learned from Jeong. Later, and in 1830, Choui who, during a visit to Seoul, shared his tea with a number of scholars. Rather remarkably, a letter about Jeong’s method of making caked tea has survived. This letter is dated 1830, and it was sent from Dasan to Yi Si-heon (1803-1860). In it, Dasan wrote, “It is essential to steam the picked leaves three times and dry them three times, before grinding them very finely. Next that should be thoroughly mixed with water from a rocky spring and pounded like clay into a dense paste that is shaped into small cakes. Only then is it good to drink.”

And it’s from these methods and techniques that Dasan taught others that helped revive tea production in the early 19th century in Korea.

Temple Layout

You first make your way towards Baengnyeonsa Temple up a forested pathway past a stately Iljumun Gate and the temple’s Haetalmun Gate. Eventually, you’ll arrive at the front facade to the main temple courtyard. You’ll need to pass under the imposing Mangyeong-ru Pavilion. The first floor of this structure acts as a tea cafe (but was closed when I visited), while the second story of the pavilion acts as a lecture hall for dharma talks.

Emerging on the other side of the Mangyeong-ru Pavilion, you’ll be greeted by the Daeungbo-jeon Hall. The exterior walls are adorned with some of the more beautiful murals that you’ll see adorning any temple shrine hall in Korea. These murals include those dedicated to Munsu-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom), Bohyeon-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Power), Agwi (Hungry Ghosts), the Moktak legend, the Shimu-do (Ox-Herding Murals), and the Bodhidharma. Additionally, there are two large-sized dragon heads on either side of the temple shrine hall’s signboard. They are ornate, colourful, and fierce.

Stepping inside the Daeungbo-jeon Hall, you’ll be greeted by beautiful wall-to-wall dancheong colours and murals. The main altar triad is centred by Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) and joined on either side by Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise) and Yaksayeorae-bul (The Buddha of Medicine, and the Buddha of the Eastern Paradise). Rather uniquely, there is no datjib (canopy) above the heads of the main altar triad. Instead, all that appears is an older wooden sculpture of a dragon-head, which is flanked on either side by a haetae and a phoenix that are equally older. The interior of this fabulous main hall is rounded out with a Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural). The Daeungbo-jeon Hall at Baengnyeonsa Temple was first built in 1762.

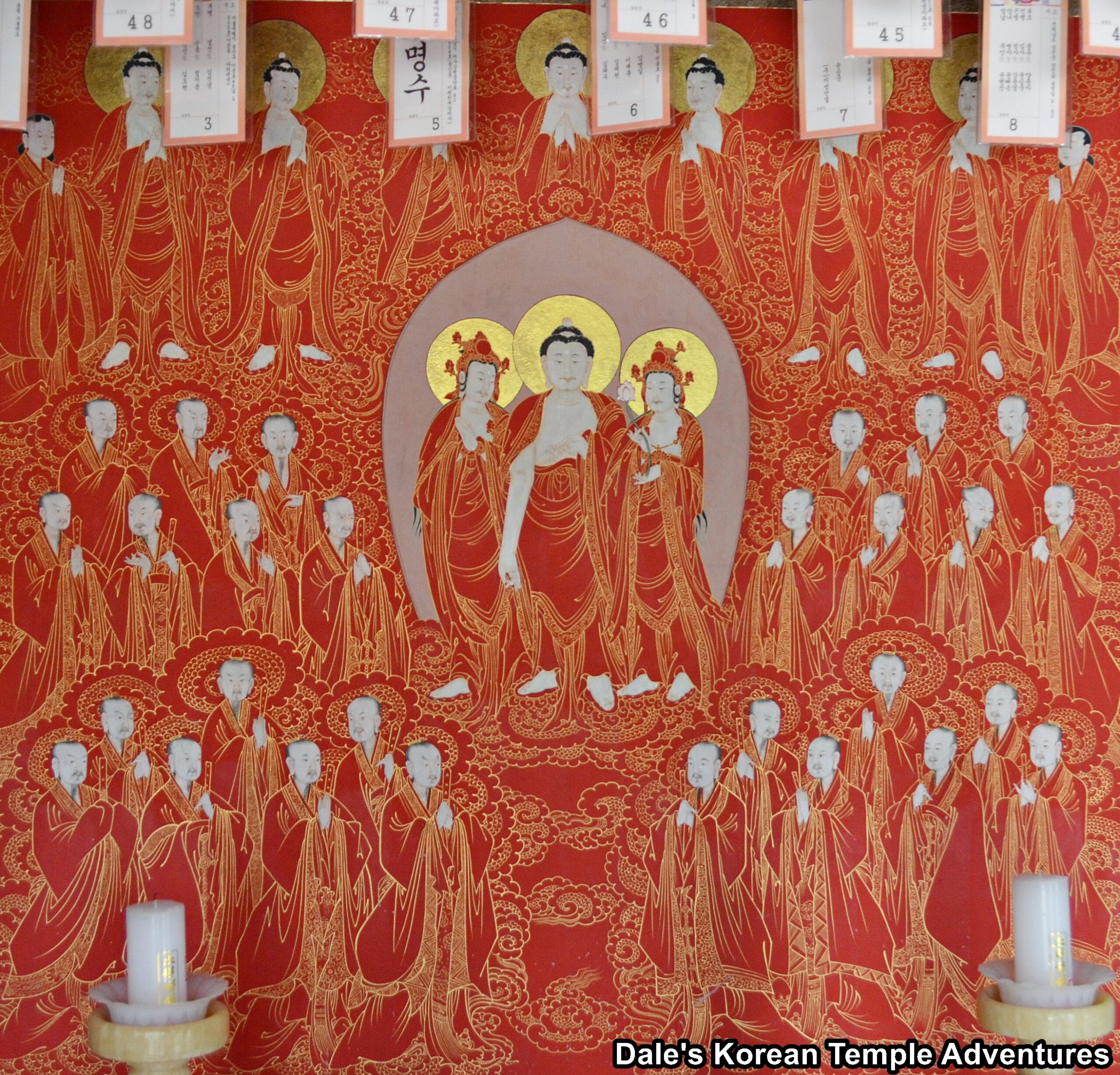

To the right of the Daeungbo-jeon Hall is the temple’s Samseong-gak Hall. In front of the shaman shrine hall, you’ll find a seokdeung (stone lantern). Stepping inside the Samseong-gak Hall, you’ll find three highly original shaman murals including the positioning of the mural. Instead of having Chilseong (The Seven Stars) hanging in the centre of the three murals, you’ll find a wonderfully large mural dedicated to Dokseong (The Lonely Saint). To the left of this mural is the mural dedicated to Chilseong (The Seven Stars). Instead of illustrating a couple of constellations, this red Chilseong mural highlights 5 different constellations in one mural. And to the right of the central Dokseong mural, you’ll find an older mural dedicated to Sanshin (The Mountain Spirit). The tiger that joins Sanshin in this mural has large bugged out eyes.

To the left of the Daeungbo-jeon Hall, on the other hand, you’ll find the Myeongbu-jeon Hall. The exterior walls to this hall, once more, are adorned with a wide variety of murals including one dedicated to King Sejo of Joseon (r. 1455-1468) and the Bodhidharma. Stepping inside the Myeongbu-jeon Hall, you’ll find a green haired image of Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife) on the main altar. The statue of Jijang-bosal is surrounded by a fiery mandorla. And to the left and right of Jijang-bosal, you’ll find seated images of the Siwang (The Ten Kings of the Underworld), as well as two statues dedicated to the Geumgang-yeoksa (Vajra Warriors) at the entry to the shrine hall.

Before making your way up to the upper courtyard at Baengnyeonsa Temple, have a look back towards the bay off in the distance. In the upper courtyard, you’ll find the Nahan-jeon Hall and the Cheonbul-jeon Hall. The Nahan-jeon Hall has a beautiful collection of Nahan (The Historical Disciples of the Buddha) statues inside and centred by a main altar image of Seokgamoni-bul. As for the Cheonbul-jeon Hall, the interior is filled with golden images of the Buddha.

To the left of the Mangyeong-ru Pavilion, and standing in the lower courtyard and past the elevated Jong-ru Pavilion, you’ll find a large wooden pavilion with a stele inside it. This is the “Stele for the Construction of Baengnyeonsa Temple,” which is the only Korean Treasure at the temple. This large stele stands 4.47 metres in height. It consists of a traditional tortoise-shaped platform, a body stone, and a capstone. The tortoise-shaped platform was first made during the early Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), whereas the body and capstone were completed in 1681. The dragon-headed tortoise platform has seven neatly arranged teeth. The long beard on its chin reaches down to its neck. The dragon-head has large, round eyes, and its shell has hexagonal patterns on it with lotus flower designs. Each of the four feet have five toes, and its tail is coiled up and turned to the left. As for the body of the stele, it contains an epitaph on both the back and the front. The inscription on the front details the history of Baengnyeonsa Temple, while the inscription on the back lists the names of the people who helped complete the stele. Finally, and as for the capstone, it has two dragons sitting back-to-back and are beautifully rendered.

How To Get There

The only way to get to Baengnyeonsa Temple from the Gangjin Intercity Bus Terminal is to take a taxi. It’ll take 15 minutes over 10 km, and it’ll cost you 19,000 won (one way).

Overall Rating: 8/10

There’s a lot to love about Baengnyeonsa Temple. And not knowing what to expect, the temple definitely surpassed my expectations. Both the interior and the exterior of the Daeungbo-jeon Hall are wonderful for a number of reasons including the murals, the main altar statues, and the dancheong inside the main hall. In addition to the Daeungbo-jeon Hall, the artwork inside the neighbouring Samseong-gak Hall are spectacular for various reasons. The views, the mature trees, the bay off in the distance, the connection to tea in Korea, and the artwork throughout the temple grounds makes Baengnyeonsa Temple a must!

Recent comments