This posts contains affiliate links. I receive a percentage of sales, if you purchase the item after clicking on an advertising link at no expense to you. This will help keep the website running. Thanks, as always, for your support!

Introduction

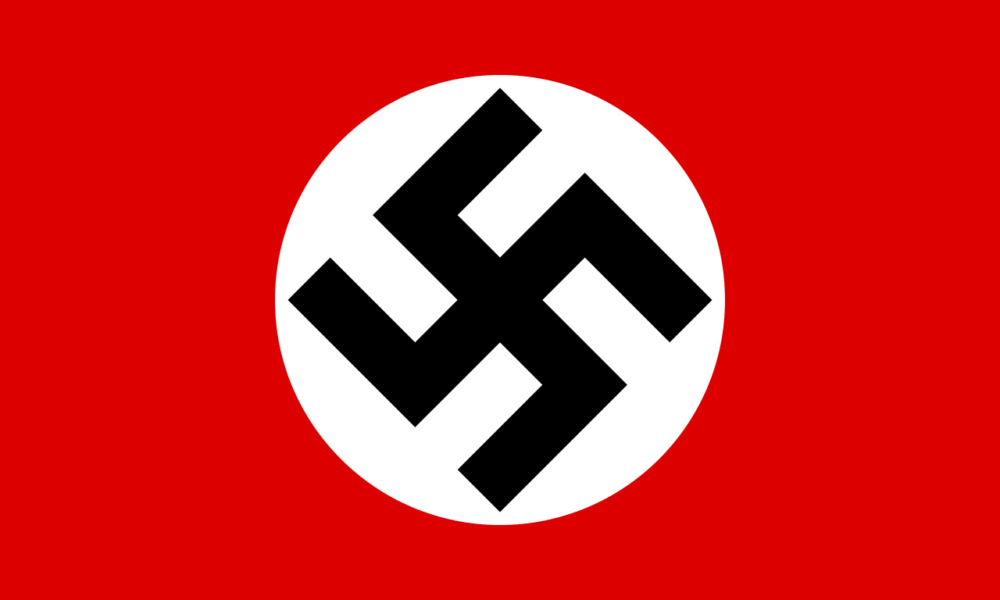

I’m sure you’ve seen the Manja – 만자 several times when you’ve visited a Korean Buddhist temple. In the West, this symbol is known as a swastika, and it has a more ominous meaning to it, unfortunately. It’s now come to be synonymous with Nazism, Hitler, and the Third Reich.

However, while the Nazi use of the swastika stands for racism and hatred, the Buddhist idea of the swastika is meant to symbolize good fortune and auspiciousness. It’s a head-spinning world of difference. So let’s take a closer look at the history of the swastika, what it symbolizes, and why you can find it at a Korean Buddhist temple.

Design

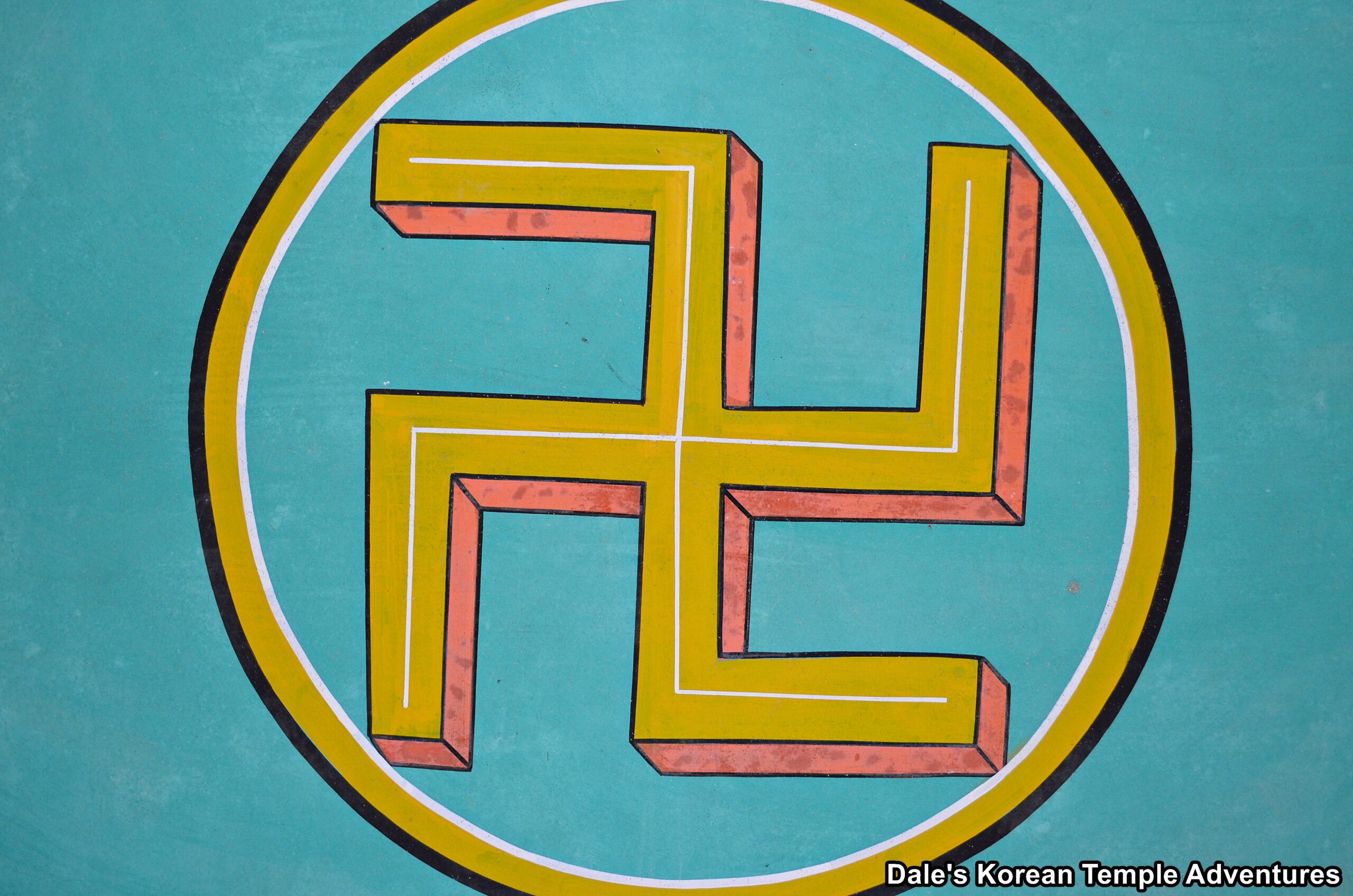

A swastika is a cross-like symbol with four arms of equal length. At the end of each of these four arms, they have a bend in them at a right angle. There are right-facing/clockwise swastikas – 卐, and there are left-facing/counter clockwise swastikas – 卍. The first use of the swastika dates all the way back to the Indus Valley civilization that existed some five thousand years ago. The swastika can be found worldwide in the art of multiple cultures like the Egyptians, Romans, Greeks, Native Americans, Persians, and East Asians. Religiously, it can be found in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. In Korean Buddhism, the swastika, which is known as a Manja, is predominantly left-facing, while the Nazi swastika is right- facing.

Meaning of the Manja/Swastika

The word “swastika” is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word “svastika.” The word is a compound word. “Su/sv” means “good or auspicious” in English, while “asti” means “it is.” And “ka” is simply a diminutive suffix.” So put together, swastika means “it is good” or “all is well” in English.

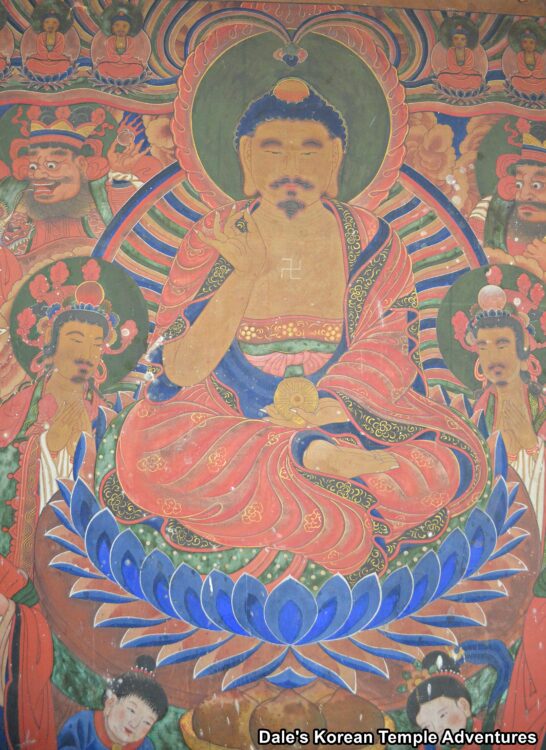

It’s common to see the swastika at the beginning of Buddhist texts much like in Hinduism. In Buddhist texts, this symbol is meant to represent universal harmony, prosperity, good luck, the dharma, long life, and the eternal. Different forms of Buddhism throughout the world have different meanings associated with the swastika symbol. It’s common to find a left-facing swastika imprinted on the chest, feet, or palms of the Buddha. It’s synonymous with the dharma wheel and the turning of the wheel. More generally, the shape symbolizes the eternal cycle of Samsara which is a core tenet of Buddhism.

The word for the swastika in Korean is Manja – 만자. The Manja is commonly used to represent the whole of creation, and the word literally means “The character for ten thousand.” Why is the number ten thousand so important? Well, “Man – 만” is a transliteration of the Chinese Character for “wàn” in Mandarin. This character variant, which is known as Hanja in Korean, has the meaning of “myriad, “all” or “eternity.” So “Man” is a homonym for both “ten thousand” and “myriad;” and hence the connection between the two words is formed.

In Sanskrit, Manja is referred to as Srivatsalksana. And while there are four different ways that this word can be expressed in Sanskrit, the most common is Srivatsa. Srivatsa, or Gilsanghuiseon (길상희선) or Gilsanghaeun (길상해운) in Korean, refers to one of the Samsipisang (삼십이상). The Samsipisang are the thirty-two marks of excellence that could be found on Seokgamoni-bul’s (The Historical Buddha) body. From his head to his toes, the Buddha was covered in these thirty-two marks of distinction.

Korean Temples

So where exactly can you find the Manja at a Korean Buddhist temple or hermitage? Well, you can find them pretty much everywhere. In fact, when you’re looking to find a temple or hermitage on a Korean map, the map symbol that demarcates a temple say from a museum is a Manja. As for the temple itself, you can find a Manja pretty much anywhere and everywhere, including temple shrine halls and Buddhist artwork. Some of the more common places to find a Manja is the ornamental painting atop the roof of a main hall. Another place you can find the Manja is adorning the chest of a painting dedicated to the Buddha or in the clothes that a Bodhisattva might be wearing.

Manja Examples

There are a countless amount of great examples of the Manja throughout the Korean peninsula. The Manja is especially prominent during Buddha’s Birthday celebrations in Korea. Here are just a few specific examples that you can find of the Manja at Korean Buddhist temples. The roof of the Daeung-jeon Hall at Samgwangsa Temple in Busanjin-gu, Busan, and the Daeung-jeon Hall at Daewonsa Temple in Sancheong, Gyeongsangnam-do. There’s also a large Manja on the ceiling of the Cheonwangmun Gate as you pass through the entry gate at Jangansa Temple in Gijang-gun, Busan. There’s a beautiful white Manja that adorns the chest of Jeseok-bul in the centre of the Chilseong (Seven Stars) mural at Naewonsa Temple in Sancheong, Gyeongsangnam-do. And the Manja symbol can be found on the feet of the large bronze statue of the Reclining Buddha at Manbulsa Temple in Yeongcheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do. As you can see, the architectural and artistic examples are nearly limitless.

Conclusion

So the next time you’re looking for a temple on a map, or you’re in fact at a Korean Buddhist temple and looking around at the architecture and artwork, you’ll know that the Manja has nothing to do with the Nazis. Context is everything! In fact, when you see a Manja at a Korean Buddhist temple, you’ll now know that it’s meant to be a symbol for good fortune and auspiciousness. So while the symbol of the swastika has been associated for too long with hate and the Nazis; hopefully, slowly but surely, it’ll be reclaimed for something far more beautiful and peaceful. And perhaps one of those vehicles for change towards peace and beauty can start at a Korean Buddhist temple.

Recent comments