Okryeonam Hermitage – 옥련암 (Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do)

Hermitage History

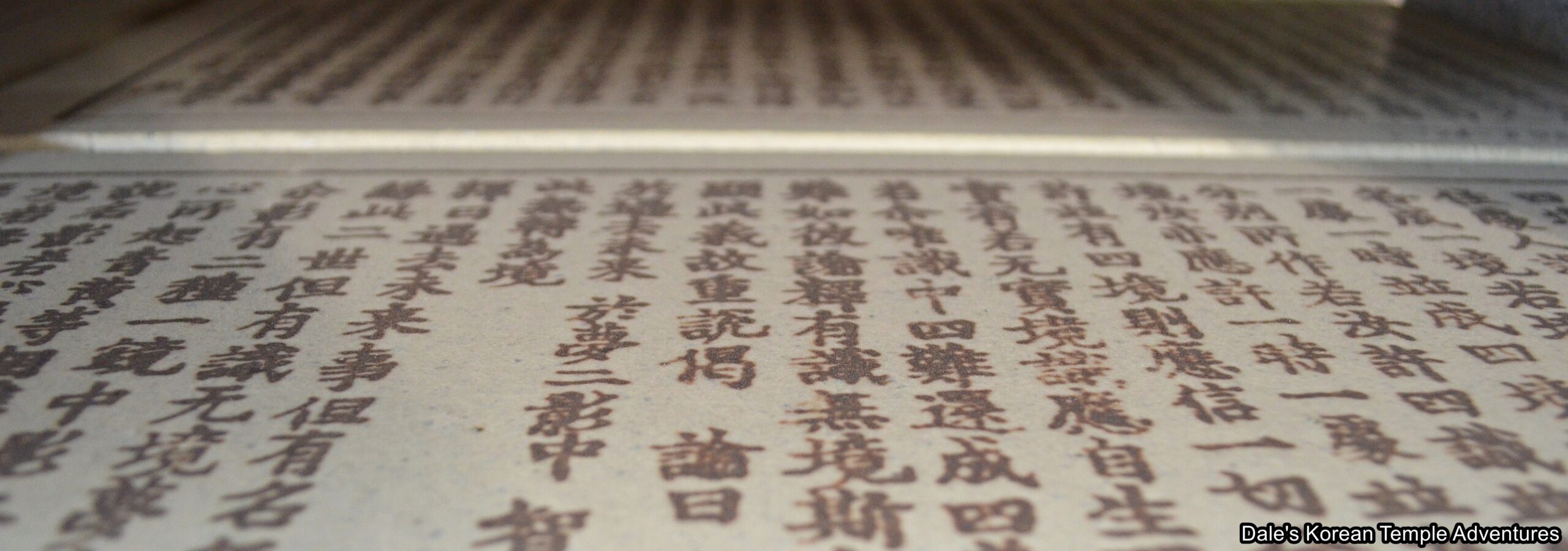

Okryeonam Hermitage is located on the Tongdosa Temple grounds in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do to the south of Mt. Yeongchuksan (1,081 m). It’s believed that the hermitage was first founded in 1374. However, there is very little known about the hermitage after it was initially constructed. Later, and in 1857, Okryeonam Hermitage was rebuilt by two monks, Hogok and Cheongjin. At this time, it was a small hermitage. Over time, it has grown. Additionally, and according to documents, the Geukrak-jeon Hall at Tongdosa Temple has a triad on the main altar. This triad was made at Okryeonam Hermitage in 1835.

There’s a rather interesting legend connected to Okryeonam Hermitage. There was a spring called Janggunsu at the hermitage, and the monks would regularly drink from it. After drinking from this spring, the monks would grow strong. Envious of this, monks at a larger temple secretly filled the Janggunsu spring and turned water away from this spring in another direction. As a result, there were no strong monks left at Okryeonam Hermitage. Rather interestingly, there is now a mineral spring at Okryeonam Hermitage that’s called Janggunsu. I wonder if you drink from it you’ll grow strong, as well. Either way, it’s a popular place for Koreans to fill up on some water either for a hike or to bring home.

Hermitage Layout

As you first approach the hermitage grounds, you’ll notice a collection of newly built cairn-like pagodas. Past these stone pagodas to your right, and as you continue towards the hermitage, you’ll notice a standing life-size statue of Podae-hwasang (The Hempen Bag). Finally, you’ll know that you’re nearing the hermitage when you start to see cultivated fields being worked by the monks at the hermitage.

In the distance, and continuing up the elevated hermitage road, you’ll see Okryeonam Hermitage. Near the hermitage parking lot, you’ll also see a sheltered area that houses the Janggunsu spring. Beyond the hermitage parking lot, and now making your way to the main hermitage courtyard, you’ll see the newly built visitors’ centre to your left.

Finally, you’ll be able to see an uneven set of stone stairs that lead into the main hermitage courtyard. There are a pair of sentinel-like pine trees that stand guard on either side of these stone stairs. The entire courtyard is beautifully maintained including diminutive wood guardian posts. Straight ahead of you, and the main hall at Okryeonam Hermitage, is the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall. The front floral latticework is beautiful. At the base of this latticework are some menacing Gwimyeon (Monster Masks). Adorning the exterior walls are two sets of murals. The lower set are the Palsang-do (The Eight Scenes from the Buddha’s Life Murals), while the upper set are various murals depicting Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha). Up in the eaves of the main hall, you’ll find wood statues dedicated to the Nahan (The Historical Disciples of the Buddha). Rather interestingly, and in the upper portion of the left exterior wall, you’ll find a signboard that reads “큰빛의집 – Keun Bit Eui Jib,” or “House of Big Light” in English. What’s rather curious about this sign is that it once hung over the main front entrance to the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall. Now, it’s been replaced by a hanja sign that reads “Daejeokgwang-jeon” over the same entry to the main hall.

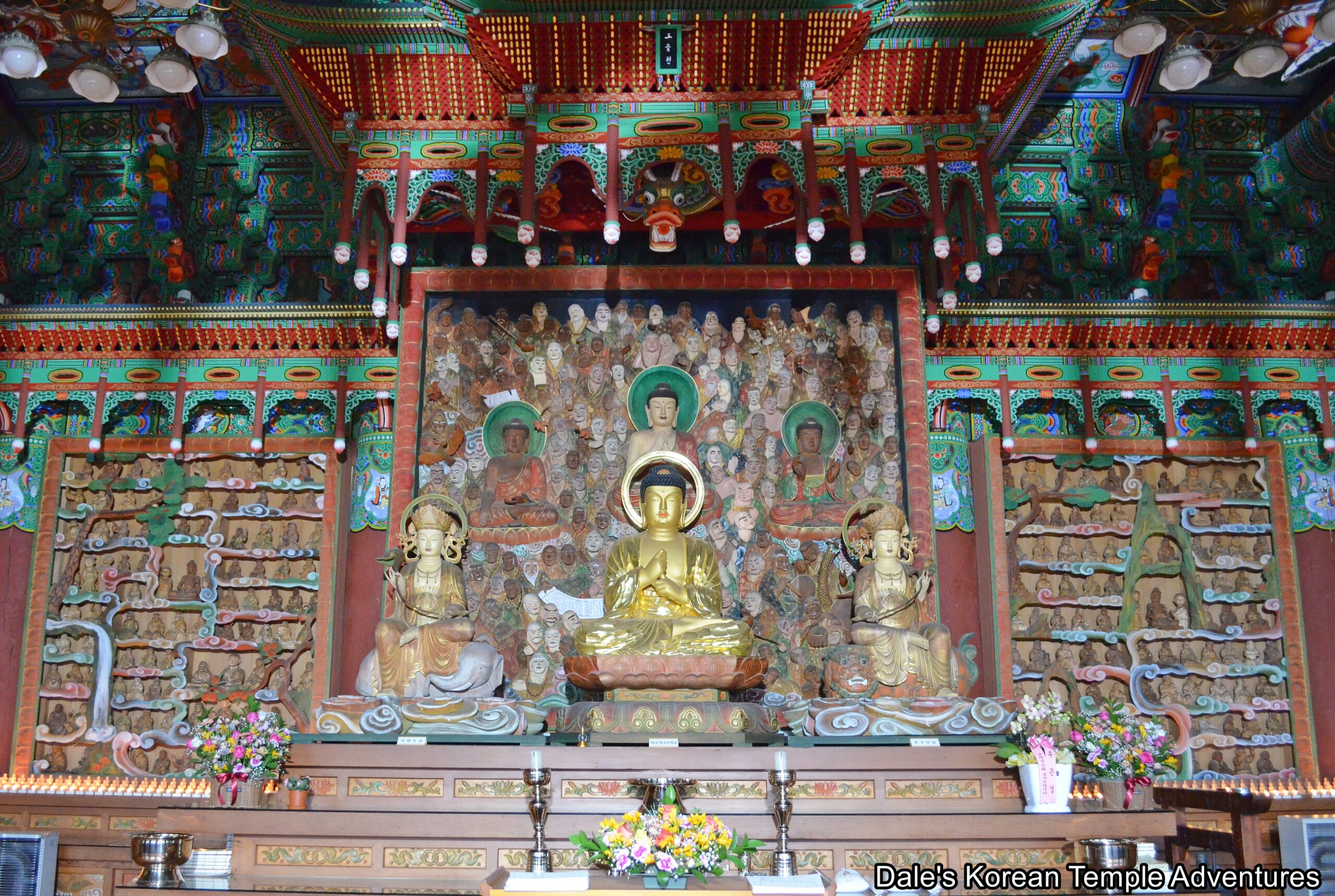

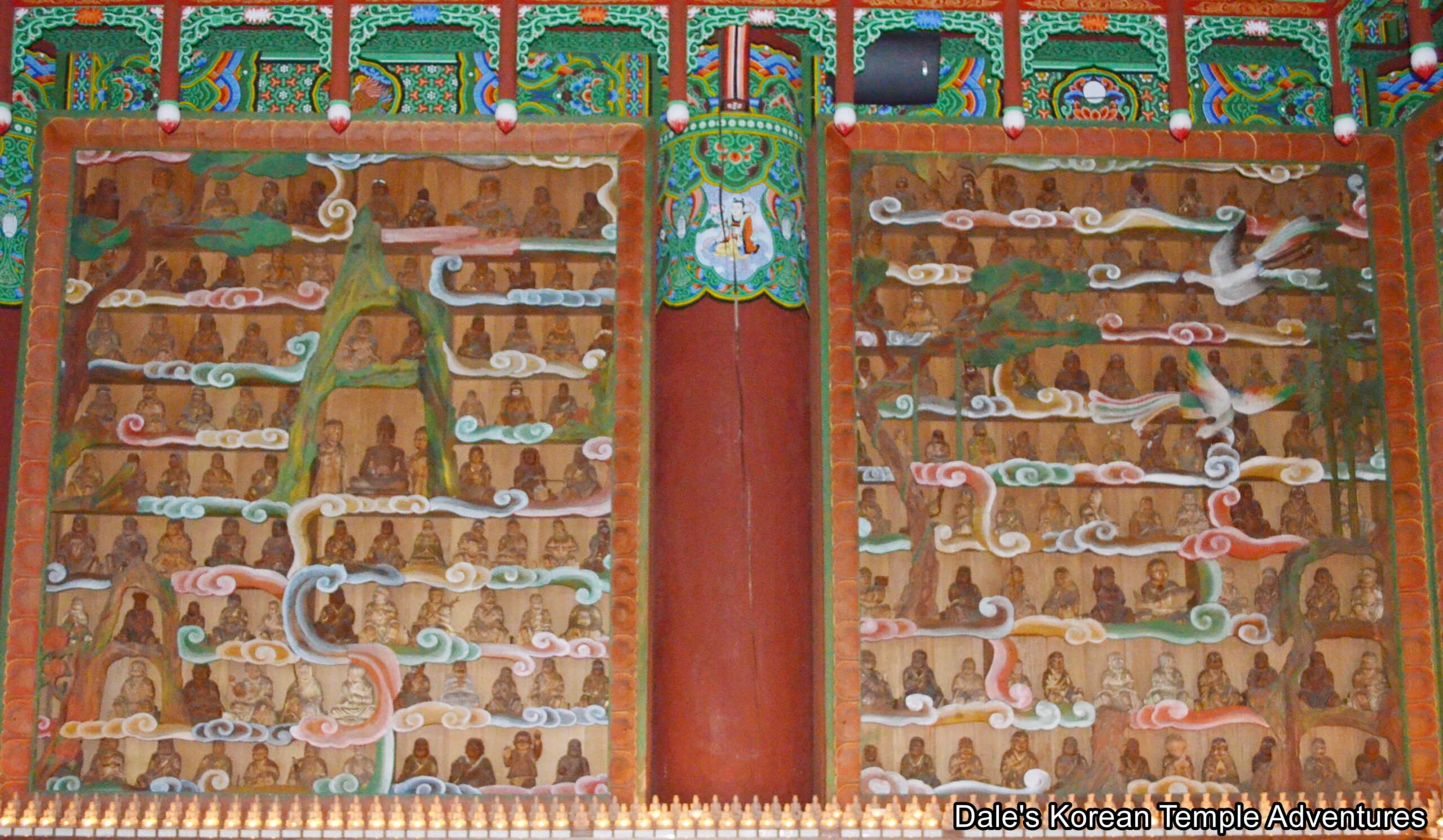

Stepping inside the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall, you’ll find a main altar triad centred by Birojana-bul (The Buddha of Cosmic Energy). Joining this central image on either side are wood statues of Bohyeon-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Power) atop a white elephant, while the other statue is dedicated to Munsu-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom) atop a multi-coloured haetae. To the right and left of the main altar, and in swirls of wood coloured clouds, you’ll find 1,250 Nahan statues. Hanging on the far right wall is a wood relief of a well-populated Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural).

To the left of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall is the Muryangsu-jeon Hall. The exterior walls to this shrine hall are adorned with simple dancheong colours. Stepping inside the Muryangsu-jeon Hall, you’ll find a main altar triad centred by Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise). And seated on either side of this central image are Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion) and Daesaeji-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom and Power for Amita-bul). Overhead of the main altar are a panel of five paintings. The central image has a pair of phoenixes. Next to this central image are two paintings. The one to the right is dedicated to a childlike Bohyeon-bosal, while the image to the left is dedicated to a childlike Munsu-bosal. And book-ending the collection are a pair of Bicheon (Flying Heavenly Deities). To the right of the main altar is a statue and wood relief dedicated to Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). And to the left of the main altar are a pair of wood reliefs. These reliefs are dedicated to Dokseong (The Lonely Saint) and Sanshin (The Mountain Spirit).

How To Get There

From Busan, you’ll first need to get to the Nopo subway stop, which is stop #134. From there, go to the intercity bus terminal. From the intercity bus terminal get a bus bound for Tongdosa Temple. The ride should last about 25 minutes. These buses leave every 20 minutes from 6:30 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. From where the bus drops you off at the Tongdosa Temple bus stop, you’ll need to walk an additional 10 minutes to the temple grounds west of the bus stop.

Once you get to the parking lot for Tongdosa Temple, keep walking up the adjoining road to the left. Follow this road for about a kilometre. The road will fork to the right or go straight. Follow the road that goes straight. Continue up this road for another two kilometres and follow the signs as you go because there is more than one hermitage back there.

Overall Rating: 5/10

The obvious main highlight to Okryeonam Hermitage are all the wood statues and reliefs spread throughout the two shrine halls. Of particular beauty are the main altar statues and Nahan statues inside the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall, as well as the shaman reliefs inside the Muryangsu-jeon Hall. Also have a look up at the eaves to the main hall at all the wood statues, as well as the wood guardian poles out in front of the Daejeokgwang-jeon Hall. There’s a lot of artistic beauty to be found at Okryeonam Hermitage some of it obvious and some of it a bit hidden, so take your time and enjoy this hermitage.

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

In addition to its technical advancements, SMILE PRO also prioritizes the patient experience. The combination of faster treatment times and improved precision translates into reduced overall procedure duration and enhanced comfort for patients. Shorter treatment time minimizes the potential for discomfort and anxiety, allowing patients to undergo laser vision correction with greater ease and confidence.

In addition to its technical advancements, SMILE PRO also prioritizes the patient experience. The combination of faster treatment times and improved precision translates into reduced overall procedure duration and enhanced comfort for patients. Shorter treatment time minimizes the potential for discomfort and anxiety, allowing patients to undergo laser vision correction with greater ease and confidence.

Recent comments