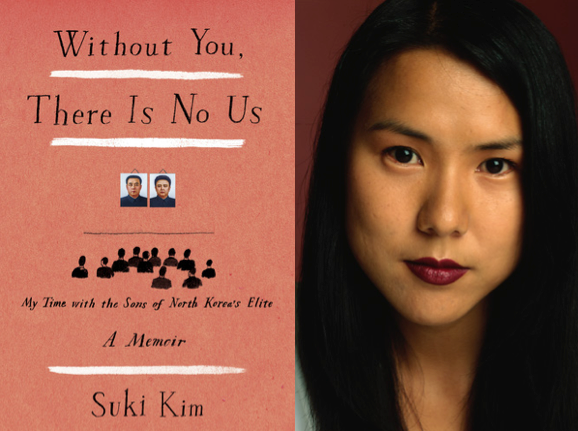

Suki Kim’s excellent new memoir Without You, There Is No Us: My Year with the Sons of North Korea’s Elite surely ranks as one of the greatest Gonzo journalistic feats ever, right up there with Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels, or Rory Stewart’s The Places in Between (about a guy who walked across Afghanistan in the months after 9/11). You think you’ve got a tough teaching gig? To get her story, Kim, a Korean-American, lived for a year in Pyongyang, North Korea, teaching English composition at the Pyongyang University for Science & Technology (PUST), a university run by Christian missionaries.

I mean—just imagine . . . having to live with Christian missionaries for a whole year!

And, sure, I guess living in a repressive totalitarian state was pretty tough, too.

Her remarkable undercover stint has resulted in one of the best books on North Korea in recent years. Without You, There is No Us belongs squarely in the first tier of works that seek to illuminate the darkness of this mysterious, closed society. To be sure, Kim’s access was limited to just a geographic and demographic sliver of North Korea. However, no book, not even the best defector accounts such as The Aquariums of Pyongyang and Nothing to Envy, detail such real, extended, relatively unscripted interaction between real North Koreans and an “enemy” American.

At first glance, there aren’t any big revelations here. Much of what Kim presents should be very familiar to anybody who has read any travel accounts in North Korea: the constant presence of the “minders” who “mind” (spy on) your every move; the “sightseeing” mostly restricted to mind-numbing, eyeball-glazing monuments to the Great Leader and Dear Leader; the endless demonization of America; the grinding poverty of a ruined economy lurking behind the paper-thin façade of modernity. This is all well-trodden territory, but Kim presents the familiar themes of barren / creepy / repressive North Korea with her novelist’s sharp eye for telling detail.

Where the book really breaks new ground, however, is in the author’s day-to-day accounts of teaching—or attempting to teach—the fully indoctrinated young men of the book’s title, the “sons of the elite.” All of her students were sons of Pyongyang’s elite ruling class (though she never talked to, let alone met, any of her students’ parents). How do you teach opinion or persuasive essays to people who have been taught—warned, even— never to argue, never to have an opinion? How do you teach them to back up their ideas with supporting evidence when “facts” or “the truth” have always been simply what the Dear Leader declares them to be? “Their entire system was designed not to be questioned, and to squash critical thinking,” Kim writes. In North Korea, “there was no proof, no checks and balances—unless, of course they wanted to prove that the Great Leader had single-handedly written hundreds of operas and thousands of books and saved the nation and done a miraculous number of things.” She sums up trying to teach essay-writing to such blinkered students in one word: “disaster.”

Simple conversations with students in the lunchroom or classroom were just as difficult and fraught with dangers. Every day was a dance through a DMZ minefield of forbidden topics. In answering students’ endless questions about the world outside their hermetically-sealed borders, Kim knew that revealing anything about the wealth, openness and freedom of “out there” was risky, for both herself and the students. A simple, honest answer to an innocuous question like “How many countries have you been to?” would let students plainly see the opportunities available to her that were utterly denied to themselves.

Yet as abhorrent and alien as much of their views, behavior and upbringing are, Kim, like any good teacher, can’t help but grow attached to them over her two semesters at PUST. She often calls the students “beautiful” and “lovely” and refers to them as “her children.” Throughout the book, Kim explores the wrenching ambivalence of wanting to open up their minds yet not wanting to get them in trouble—either as students or in the future when they would supplant their parents as the top-echelon leadership of the DPRK. In dealing with one particularly inquisitive student, Kim and her young T.A. Katie realize that saying too much might get themselves deported, but could very well get the student killed. “Until then, I had hoped that perhaps I could change one student, open up one path of understanding,” Kim muses. “But what kind of a future did I envision for the one student I reached? Opening up this country would mean sacrificing these lives. Opening up this country would mean the blood of my beautiful students.”

Her portrait of her students is fascinating, empathetic, and immensely sad. In South Korea, foreign English teachers often bemoan their students’ lives that are equal parts grindstone and pressure cooker, yet the most haggwon-oppressed, sleep-deprived South Korean student would not survive a week in the shoes of Kim’s North Korean students. They are never alone—never, not a single moment. They are partnered up in a “buddy” system for the clear purpose of keeping an eye on one-another. It’s breathtaking how carefully the State raises a population of snitches. Also heart-rending is the physical labor that students are submitted to—most of it either pointless or made pointlessly difficult by the absence of tools or technology: cutting crass with scissors; standing guard in freezing cold weather over the ridiculous shrine to “Kimjongilism;” being carted off during school vacations to work in harvesting or construction sites. Even as sons of high-ranking party members, life is an brutal, endless slog, even if they will never face starvation. For them, attending a weekend math haggwon would be like lounging pool-side with a fruity drink.

Despite the glibness of my lead graph, living with Christian missionaries was, for Kim, its own brand of, well, hell. At times, her evangelical colleagues spur as much forehead-slapping disbelief and anger as the North Korean authorities. When Kim wants to show students a Harry Potter movie, the idea is shot down not by the North Korean officials (who must approve every book and every lesson plan), but by the school’s head teacher who calls it a piece of anti-Christian “filth.” “What would Christians around the world say about our decision to expose our students to such heresy?” the woman rages with staggeringly misguided righteousness.

At one point, a colleague openly talks with Kim about how her reason for being there was to “bring the Lord to this Land,” how “this life here is temporary,” and that the suffering North Koreans “will be received by Him in heaven.” Kim explodes at her, accusing her of delegitimizing the suffering of the North Korean masses: “So are you saying that it’s okay for North Koreans to rot in gulags because in your estimation it isn’t real? . . . If the eternal life waiting for them in heaven is so amazing, should the millions who are suffering here just commit mass suicide? Why don’t you go check out a gulag and then dare to tell me that it’s temporary?”

Kim’s portrayal of the school and its Christian faculty has garnered some controversy. The school has openly expressed hurt and anger over what they call a betrayal by Kim. They deny that they are Christian missionaries at all, and that Kim both misrepresented them in the book and misrepresented herself when she landed the job.

On her website, Kim counters these charges with a simple, powerful statement:

There is a long tradition of “undercover” journalism—pretending to be something one is not in order to be accepted by a community and uncover truths that would otherwise remain hidden. In some cases, this is the only way to gain access to a place. North Korea, described only recently by the BBC as “one of the world’s most secretive societies,” is such a place. [….] I did not break any promises. I applied to work at PUST under my real name. I was not asked to sign and did not sign any kind of confidentiality agreement, nor did I ever promise not to write about PUST. Meanwhile, in the six decades since Korea was divided, millions have died from persecution and hunger. Today’s North Korea is a gulag posing as a nation, keeping its people hostage under the Great Leader’s maniacal and barbaric control, depriving them of the very last bit of humanity. So what are our alternatives? How much longer are we going to sit back and watch? To me, it is silence that is indefensible. (read the full statement at http://sukikim.com/ethicsnote)

Given the fact that Kim didn’t hide anything about her past or her career, it’s strange she got the job at PUST in the first place, a point she also makes in the book and in the full text of the above statement. She wrote several articles for Harper’s and The New York Review of Books about previous trips to North Korea, most notably an outstanding account of the New York Philharmonic’s trip to Pyongyang in 2008. That article, unlike a lot of the accounts in the mainstream press, dug underneath the official North Korea-sanctioned feel-good story of “we’re not here for politics / music can bring us together!” Instead, Kim focused on the pointlessness of interaction with North Korea when the interaction was entirely on their terms. Also, her well-received debut novel, The Interpreter, has enough sex to make a evangelical Christian blush (which is to say, any sex at all). Ten minutes of internet browsing might have suggested to school authorities what Kim had in mind in seeking this job. Equally puzzling was North Korea granting her another Visa after those earlier articles—they even assigned to her one of the same minders from the New York Philharmonic trip.

Indeed, Kim worrying about having her cover blown—by both the North Koreans and her Christian colleagues—makes her day-to-day life even more stressful and adds another layer of dark tension throughout the book. In the end, the tension, the stress, the isolation, the bleakness, the cold, and the unceasing vigilance of the State—Orwell’s Big Brother incarnate—grind down her spirit of resistance, as it all was surely designed to: “The sealed border was not just at the 38th parallel, but everywhere, in each person’s heart, blocking the past and choking off the future. As much as I loved those boys, or because of it, I was becoming convinced that the wall between us was impossible to break down, and not only that, it was permanent.”

However, in an incredible coincidence, on Kim’s very last day at the school—a day filled with the bittersweet teacher-student goodbyes that any of us who have taught for a living might recognize—something happens that suggests just maybe that this wall might one day vanish into history: Kim Jong-il dies. Her final glimpse of her students as she’s leaving for the airport is of them in the cafeteria eating breakfast, refusing to look at her, “their eyes swollen and red, [with] no expression on their faces. It was as though the life had been sucked out of them.” She makes no comment on whether or not these tears are real or forced, or perhaps some of both, but simply wonders if their world will change for the better. Three years later, we’re still asking that question.

Recent comments