This is a local re-post of an essay I wrote for the Lowy Institute last month. Basically Trump is shifting the entire debate on responding to North Korea to the right.

Broadly, I would say there a two camps – hawks and doves – within the Korea analyst community. And each of those has a nested sub-division – moderates and ultras. The dove ultras are basically pro-Pyongyang. There aren’t too many of these folks left, no matter how mccarthyite the South Korean right gets. Then come the moderate doves who want engagement and the Sunshine Policy. On the right, the moderate hawks (I put myself here) are skeptical of engagement but accept trying, focusing more on sanctions and China. And the hawk ultras want to bomb the North.

Trump’s big impact on North Korea debate is to legitimize the hawk ultras and push the entire conversation their way, in the process writing the doves out of the conversation entirely debate. I have half-in-jest referred to this as the ‘Kelly Rule’ on Twitter. The American debate is increasingly a contest between bombers ultras, like John Bolton yesterday in the WSJ, vs panicked moderate doves and hawks forming a united front to prevent a war.

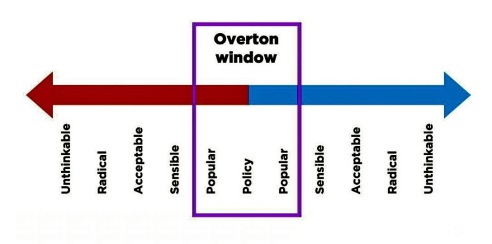

In social science language, Trump is pulling the Overton window toward strikes, making them more likely generally, even if they don’t happen this year. Trump is normalizing or legitimizing discussions of (the hugely risky) use of force against North Korea.

The full essay follows the jump…

It is a weird time on the Korean Peninsula. Last year saw an extraordinary ramp-up in tensions. US President Donald Trump used incendiary rhetoric for months. His national security staff stated repeatedly that North Korea’s possession of a nuclear missile was unacceptable, and that the nuclear deterrence which worked throughout the Cold War was impossible with the North. But Trump himself did not stop there.

It is now known that his most explosive comments about the North – the use of “fire and fury” to “totally destroy” the “Rocket Man on a suicide course” – were ad-libbed. That is, Trump purposefully raised the temperature, and within the Korea analysis and foreign policy community a sincere debate broke out about whether the US actually wanted a conflict. Was Trump looking for a fight (as he seems to want with Iran, and with the Democrats at home)?

January, however, has seen a sudden swing to the reverse. Now the talk is all about North Korea’s participation in the upcoming Pyeongchang Olympics in South Korea. Northern and Southern negotiators are meeting, and there is much hope in the left-progressive press here that an “Olympic spirit” will carry over from sporting events to the negotiating table. “Sports diplomacy” is all the rage, and the South Korean conservative press is sufficiently unnerved by the sudden diplomacy hype that it is already running cranky (but accurate) editorials about giving away too much when talks have scarcely started. (My personal favourite: “Will S. Koreans Go Crazy Over Some N. Korean Apparatchik?”)

Indeed, there much hope regarding the Olympics. I am sceptical, but we should, of course, always talk to the North when possible. North Korea is the most dangerous country in the world, and we should engage with it in the hope, however unlikely, that we can pull it at least a little towards international norms.

Even if we cannot convince them to denuclearise (and we cannot), at least talks let us bring up other pressing issues, such as nuclear safety, international criminality, access to prisoners, and so on. And South Korean President Moon Jae-in was wise to credit Donald Trump, however preposterously, with North Korea’s return to negotiations. Nothing moves Trump like flattery, and with this Moon adroitly dialled down the pressure from Washington.

But even if the Olympics, the talks, Moon conning Trump, and the rest forestall a US strike on North Korea this year – strikes in 2018 were the big rumour late last year – Trump has nonetheless moved the debate significantly in favour of such strikes. Even if there are no airstrikes this year, the overall likelihood of a strike at some point has risen. Discussing the bombing has become normalised in way unseen since the 1994 US debate on striking the North.

The uptick in discussion over striking North Korea has been noticeable throughout the West, but most evident on US cable channel Fox News. But even in more serious outlets, such as Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy, the debate about strikes has cropped up.

It has been raised here, at the Lowy Institute, too. In my own media and consulting work, I am asked far more about striking North Korea than ever before: Will it happen? Should we do it? Can it be done without starting a war? Only last month I was in China for a UBS event where this issue dominated my panel. Even the market is now paying attention to the debate.

Conservative media is, naturally, the most aggressive on the topic, and here too the tone of the debate has shifted. Instead of questions about sanctions and vague threats of war, I now routinely field questions about whether we can or should strike North Korea. The “bloody nose” option is now a staple discussion topic. To capture just how common the discussion of striking North Korea became last year, I coined, half in jest, the “Kelly Rule” on Twitter. I list op-eds advocating strikes, often in a grossly flippant manner. Surely there are more that I have missed.

The upshot of all this is a movement of the discussion on North Korea to the right. Where under the Obama administration few op-eds advocated strikes, they are now proliferating. While I cannot recall conferences from a few years ago where this was a serious topic of discussion, it is now discussed at every event related to North Korea that I attend.

The debate in the West on the North Korean nuclear program is boiling down to one between hawks – moderates arguing for diplomacy and deterrence, even though we are sceptical of the former and dislike the latter with a state as awful as North Korea – versus ultras who can now find space in print to demand strikes. Doves are being written out of the conversation altogether.

The social science notion of the viability of political discussion is known as the “Overton window”. The outer limits of morally permissible discourse move over time. Leaders, technology, shifting norms in other areas, and so on can change what we are “allowed” to say, and what others consider a reasonable position worthy of debate.

Race is an obvious example. Fifty years ago it was OK to oppose interracial marriage or desegregation. In contemporary times, such thinking is excluded, to the far right, from accepted discourse. And on North Korea, Trump’s biggest contribution so far is moving the Overton window to the right.

That we are even having a protracted public debate over striking North Korea is a marker of Trump’s (and his administration’s) shifting of the terms of the debate. For the past decade, the discussion was between hawks and doves over how harshly to sanction North Korea (the right answer, by the way, is very much so). Now those moderate sanctions hawks are lining up with doves to hold the line against the ultras’ hugely risky flirtation with the “bloody nose”, or even war.

This debate will continue as long as Trump, with his penchant for belligerence and militarism, is president. Even if there is no strike on the North this year, it is more likely to happen than at any time during the past 25 years. Trump is resetting the terms of the debate.

Assistant Professor Department of Political Science & Diplomacy Pusan National University @Robert_E_Kelly |

|

Recent comments