Introduction

While perhaps not as common as tigers or dragons in Korean Buddhist artwork, the image of elephants is still quite prevalent. Whether it’s on stupas, paintings, or sculptures, the elephant can be seen at Korean temples if you look close enough.

History of Elephants in Buddhism

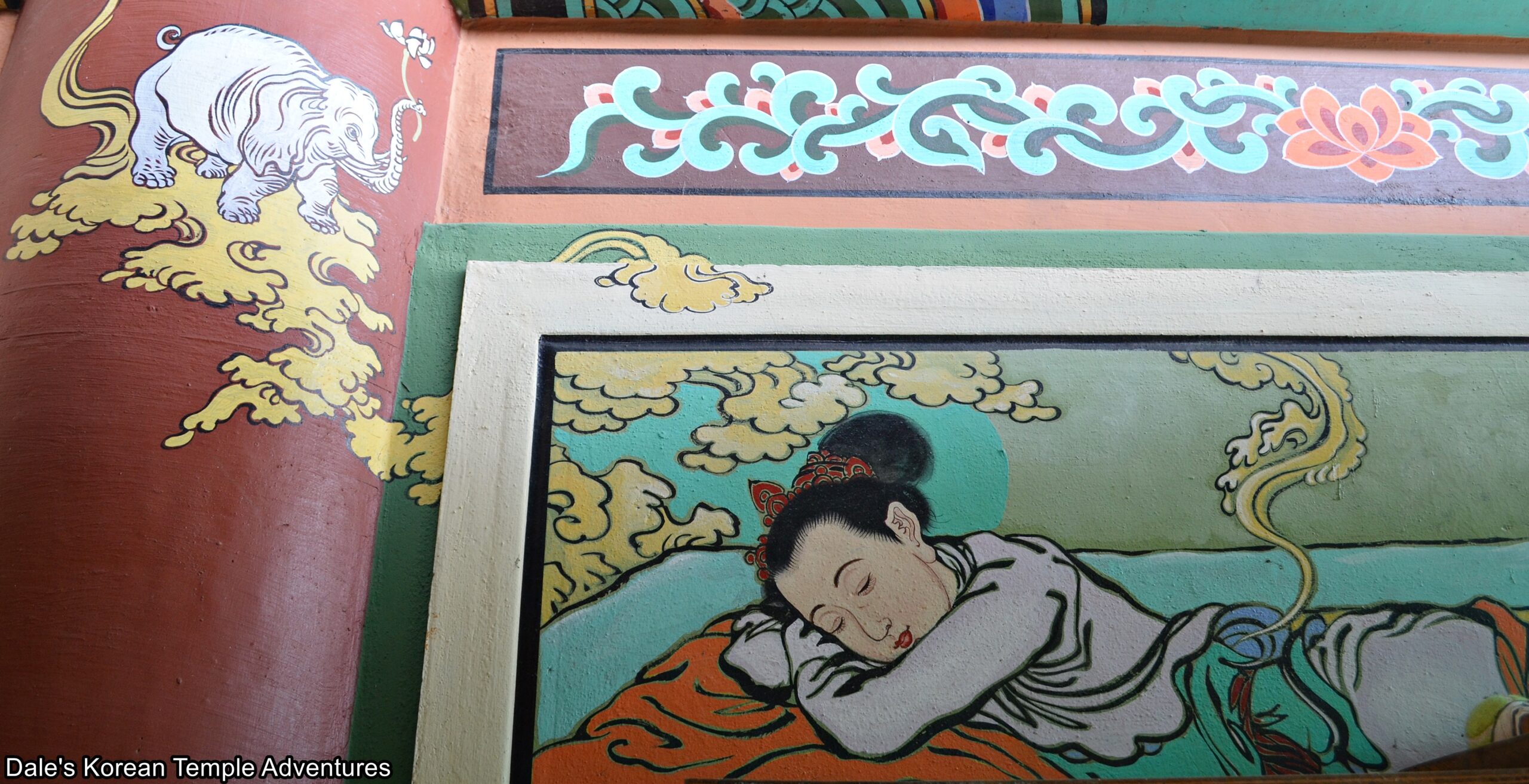

According to a Buddhist legend, one night during a full moon, and while sleeping at the palace of her husband Śuddhodana, the queen, Queen Maya had a vivid dream. In this dream, she felt carried away by the Four Heavenly Kings to Lake Anotatta in the Himalayas. After being bathed in the lake by the Four Heavenly Kings, the four kings clothed the queen in heavenly clothes, anointed her with perfumes, and provided her with divine flowers. Soon after a white elephant, holding a white lotus flower in its trunk, appeared and went around her three times. Eventually, this elephant entered her womb through her right side. The white elephant disappeared and the queen awoke. Having awoken from her sleep, Queen Maya knew that she had been presented with an important message. And it’s from this origin in Buddhism that elephants come to symbolize greatness.

Another example of the elephant in early Buddhism can be found in the disciple Sariputta, when he likens the guiding spirit of Buddhism to the footprint of an elephant. From the “Maha-hatthipadopama Sutra: The Great Elephant Footprint Simile,” it reads, “Ven. Sariputta said: ‘Friends, just as the footprints of all legged animals are encompassed by the footprint of the elephant, and the elephant’s footprint is reckoned the foremost among them in terms of size; in the same way, all skillful qualities are gathered under the four noble truths.’”

Additionally, in the early stages of Indian Buddhist sculptural art, the Buddha is symbolized as a Bodhi tree, the Wheel of the Dharma, and as an elephant. Thus, the elephant serves as a symbol of Buddhism. This is most notably seen at the Sanchi Stupa in India. It was originally commissioned by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century B.C. There are numerous examples throughout the stupa, but perhaps the most noticeable elements are on the Eastern Gateway pillars. In all, the elephant carvings at the Sanchi Stupa are royal mounts, symbols of Buddhism, simple ascents, and mythological creatures. But already, and quite early on, elephants played a central role in the imagery of Buddhism.

Symbolism of Elephants in Korea

Like so much of Buddhism, the symbolism found in the imagery of the elephant would move eastward, first through China and then onto the Korean Peninsula and Japan. In Korean Buddhism, the elephant is mean to symbolize strength, patience, loyalty, and wisdom.

In Korea, and like the white tiger, elephants were meant to symbolize rulers. However, elephants were and are considered to be more beloved because they can be tamed. Additionally, while elephants embody the idea of wisdom put into action, lions often represent decisive judgment and action based on wisdom.

Outside the tiger and the lion, elephants also appear alongside the dragon in Korean Buddhism. One of the most likely reasons for this is that the elephant is easier to draw or sculpt than that of the lion. Otherwise, it’s not easy to understand why elephants are often paired with dragons to form familiar Buddhist groupings, especially when lions may appear to be a more suitable option. This is particularly true given the widespread use of the phrase “dragons and tigers,” referring to two equally powerful opponents or entities.

Elephants at Korean Buddhist Temples

There are numerous wonderful examples of elephants appearing in the artwork of Korean Buddhism. Here are but a few of these examples:

Perhaps one of the most notable images is that from the Palsang-do (The Eight Scenes from the Buddhas Life Murals) that typically adorns the main hall of a temple. The first from this set is entitled “The Announcement of the Imminent Birth.” In this painting, Queen Maya becomes pregnant after she has a dream of a white elephant. The white elephant is offering her a white lotus from its trunk. After this, the white elephant then circles Queen Maya three times and then enters her womb with its tusk. Upon waking, Queen Maya realizes that she has experienced something spiritual. A Brahmin was consulted to interpret the significance of this white elephant dream. The Brahmin said, “A great son will be born. If he renounces the world and embraces a religious life, he will attain perfect enlightenment and become the saviour of this world.” A wonderful example of this painting can be found inside the Daegwangjeon Hall of Sinheungsa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do. In total, there are four of the eight paintings from the Palsang-do from the mid-17th century inside the main hall at Sinheungsa Temple. They are the first, fourth, fifth, and eighth, and they are stunning.

Another painted image, or even statue, is that of Bohyeon-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Power). Like the Hindu god Brahma, Bohyeon-bosal appears atop a six-tusked white elephant. If Bohyeon-bosal appears as a statue, he’ll be mounted on a six-tusked white elephant inside a Geumgangmun Gate. This is typically the second of five potential entry gates at a temple. In this gate, Bohyeon-bosal appears as a child-like figure. A wonderful example of this can be found at Ssanggyesa Temple in Hadong, Gyeongsangnam-do. As for the painting of Bohyeon-bosal, he can appear in a number of incarnations, so he can be quite difficult to discern. However, the easiest way to distinguish Bohyeon-bosal from other Buddhas and Bodhisattvas is that he’s typically mounted on a white elephant. Perhaps the most stunning example of this can be found inside the Daeung-jeon Hall at Jangyuksa Temple in Yeongdeok, Gyeongsangbuk-do. This image dates back to around the mid-18th century, and it is part of a collection of 18 historic murals inside the main hall.

As for sculptures of elephants, you can find them in various mediums like wood or stone. And they can be highly stylized in form. A good example of this can be found inside the Bulimun Gate at Tongdosa Temple in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do. If you look up at the rafters of the interior of the structure, you’ll find a white elephant facing out towards an orange tiger. Not only are they great images, but they encompass the very concept of the Bulimun Gate, which is known as the “Non-Duality Gate” in English. Basically what this means is that there is no idea of hard vs. soft, or love vs. hate; instead, all things are one. And these oppositional forces are wiped away once passing through the Bulimun Gate. And in the same context, the white elephant, which symbolizes Buddhism, and the orange tiger, which symbolize Korean shamanism, are no longer two entities; instead, they are one and the same.

And yet another sculpted example can be found at the base of a modern stupa at Jukrimsa Temple in Yeongcheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do. Housed inside this stupa are the remains of a monk. With the elephants at the base of this stone structure, it’s meant to symbolize the idea of wisdom. And through the preservation of these stone monuments, and the way in which Seon Buddhism acts is through the transmission of a teacher’s wisdom/teachings to that of his/her students.

Korean Buddhist Sangha (Community)

As for the monastic sangha (community) in Korea, the very idea of the elephant seeps into the very language. One example of this can be found in an idiom in Korea. During the “angeo,” which is a three-month long intensive retreat for Korean Buddhist monastics, the temple assigns roles and task to all those that participate. This information is then compiled into a chart and displayed as a public notice on a plaque known as the “dragon-like elephant list.”

This “dragon-like elephant” imagery is meant to motivate monastics to practice with the same fearlessness and endurance as this mythical creature. As a result, it’s a fitting name for those devoted to the three months of intense seclusion and meditation.

Conclusion

While not as common to see as other animals, whether real or imagined, like the tiger, lion or dragon, the elephant plays an important part in the symbolic imagery found within Korean Buddhist art. The ideas of strength, patience, loyalty, and wisdom are bound by the symbolic imagery of the elephant. And these images can be found in the forms of stupas, statues, paintings, and various other imagery. So while you might need to look a little closer for these elephants, they are definitely out there to be enjoyed.

Recent comments